Trump, Musk want to curb FEMA. Its North Carolina response says volumes.

Loading...

| Bat Cave, N.C.

Lynette Staton’s first thought as she descended a mountain trail after massive floods here in North Carolina in September was “Bat Cave is gone.” Her second: “Time to get to work.”

Ms. Staton wasn’t alone in her determination as platoons of relief workers – neighbors and strangers, firefighters and Mennonites – toiled together in a remarkable mass effort across a broken landscape where 74,000 buildings were damaged or destroyed, and 50 million cubic yards of debris were scattered through valleys.

Largely missing then and now in this unincorporated village, named for its mountain fissure where bats live, are folks wearing Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) caps, says Ms. Staton.

Why We Wrote This

Federal efforts to respond to disasters are facing heavy criticism. North Carolina’s flood recovery shows that FEMA’s role matters but must include improved outcomes and reforms.

It is emblematic, in Ms. Staton’s view, of the federal response here in North Carolina: The first government person she saw after the flood was a National Guard member. She asked him to help her carry some belongings across a makeshift bridge.

“He apologized but said he was there to take photos for FEMA,” says Ms. Staton, whose curiosity shop, HipHen Uniques, is now a relief center. “He said he’d come back the next day to help. I never saw him again. I could say more, but I won’t.”

Precise photo records can be critical for emergency workers to triage catastrophe responses. But small acts like not putting the camera down to help someone in a desperate situation, she says, have fueled the frustration expressed in President Donald Trump’s executive order last month, condemning the federal response headed by FEMA as too slow, bureaucratic, and politicized.

“FEMA has turned out to be a disaster,” he said during a visit to North Carolina.

Cameron Hamilton, President Trump’s new acting head of FEMA, said otherwise. FEMA “is a critical agency which performs an essential mission in support of our national security,” he wrote in a recent note to his staff.

The agency has the subject of fierce controversy and a target of the Trump administration’s accusations of government ills. On Monday, FEMA’s acting head said he had suspended FEMA payments to New York City after Elon Musk claimed that the agency paid $59 million “to luxury hotels in New York City to house illegal migrants.” The city noted that the payments were appropriated by Congress to help shelter migrants, according to news reports. On Tuesday, the agency announced it was terminating four FEMA employees for “circumventing leadership” in making hotel payments.

Here in North Carolina, the Appalachian flood recovery to date offers insights into that debate – including that even hurricane-tested North Carolina cannot handle a catastrophe like Helene. That suggests that FEMA, as it considers reforms, must address how it can be more effective and how it can help places become more resilient.

“People often say that disasters are windows of opportunities – a time to reimagine and fix things that are broken,” says Aaron Clark-Ginsberg, a policy analysis professor at the Pardee Rand Graduate School in Santa Monica, California. “But we can also lose attention and forget” what we’re working toward.

For FEMA, part of the problem is also public misconceptions. Often, the agency is supporting relief efforts by other government personnel who don’t wear FEMA caps. And while the agency assists with recovery, it was never designed to provide full funding toward that goal. Meanwhile, some increasingly extreme weather events are placing new demands on the agency.

After days of warnings, Hurricane Helene, by then a tropical storm, dumped of water on the southeastern United States Sept. 27, destroying most of Bat Cave, population 300, and other towns and places across western North Carolina. Over 100 people died in mudslides and rushing whitewater. Thousands of families remain displaced.

Four months later, in Bat Cave, progress is painfully slow. “We don’t need clothes donations. We need bulldozers and people to run ‘em,” says volunteer Ben Holmes, an HVAC mechanic from nearby Hendersonville.

Mission and focus

Much of residents’ frustration here and throughout this mountain region has landed on FEMA, an agency created in the 1970s by the late President Jimmy Carter to manage federal resources and write reimbursement checks when a state asks for help. The agency employs over 20,000 people and juggles dozens of national disaster declarations.

But rarely has the agency faced the nation’s recent one-two punch of flooding in the East and fires in the West, and then the uppercut blow of partisan political pressure from the White House. President Trump’s order created a commission to review the agency’s performance regarding Helene.

“I think, frankly, FEMA is not good,” the president said during the same remarks in last month. He suggested, offhandedly, “fundamentally reforming or maybe getting rid” of it.

To critics, FEMA has “lost mission focus,” as President Trump’s executive order claimed. They point to the FEMA worker in Florida who was fired during the Helene response for suggesting that colleagues should ignore victims with Trump flags in their yards.

Blatant politicization doesn’t jibe with what many first responders say they see on the ground in North Carolina. But the deeper critique is fair, says Susan L. Cutter, author of “American Hazardscapes.”

“Because FEMA was doing a reasonably good job of responding to disasters, there was more and more put on its plate, diluting some of its core missions,” she says. “That has happened at a time when more disasters are going on.”

Bat Cave, meanwhile, became a nexus of misinformation that helped fuel a national barrage of criticism of FEMA and the Biden administration, led by Mr. Trump.

In December, a local sheriff posted a lengthy Facebook video correcting misinformation from an influential TikTok video creator about a Bat Cave road being blocked by FEMA. The roadblock was, in fact, due to a private property dispute.

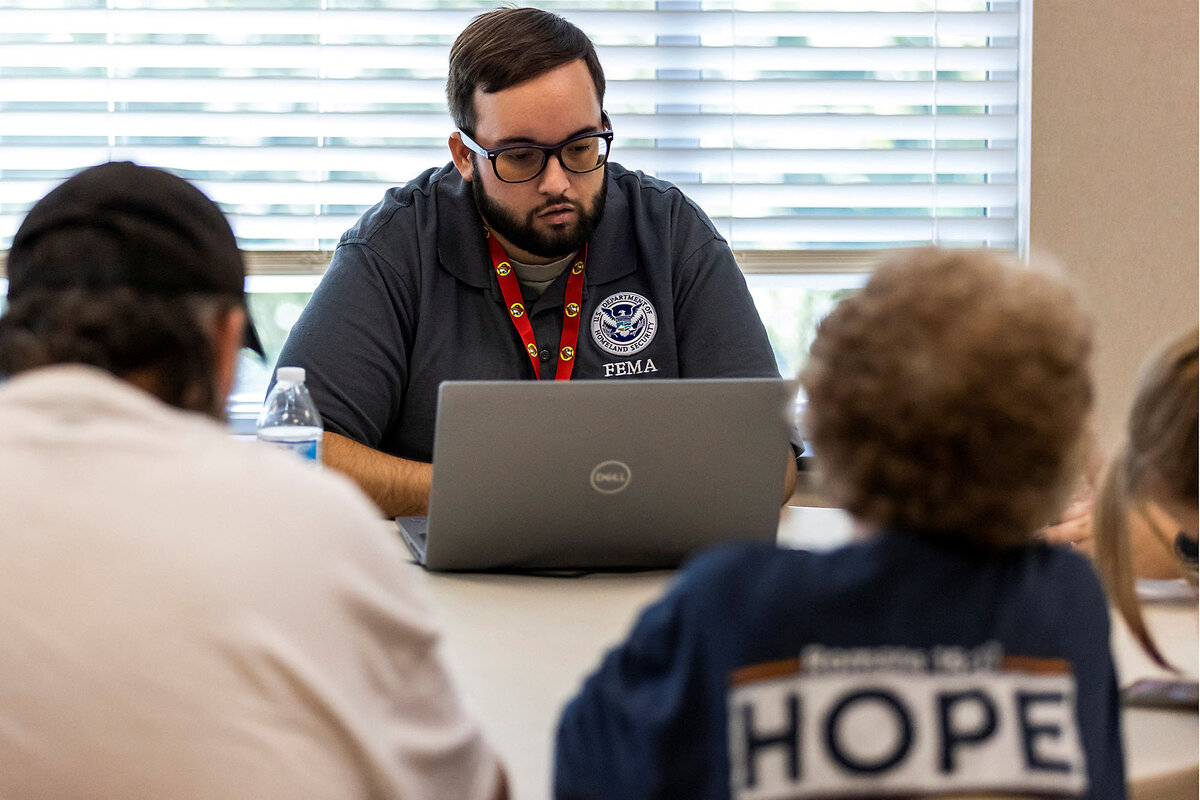

As of November, over $244 million in FEMA individual assistance funds had been paid out to nearly a quarter million North Carolinians. At the height of the recovery, some 2,000 FEMA personnel were on hand in the state to help, seeking out victims in places from shelters to neighborhoods. “They can be identified with their FEMA logo apparel,” an agency fact sheet says.

FEMA’s faltering, fact or fable?

Still, there’s a feeling among some Bat Cave survivors that it is “like we are in the land of the lost,” as Mark Staton, Lynette’s husband, says.

Ms. Staton says she has applied for but has been denied assistance. “After a while, you just give up,” she says.

Such reactions stem in part from the law’s constraints on FEMA – and strict budgetary oversight by Congress and government auditors. The agency can award individual cash assistance of just over $40,000, enough for repairs but not for a new home.

As disasters become more frequent and insurance costs rise, federal programs seem inadequate, if not useless. After all, very few people have flood insurance – only in one of North Carolina’s flooded counties, for example – and many of them are middle-income residents ineligible for rebuilding grants that focus on low-income Americans.

“How are we going to fill that hole?” asked North Carolina Rep. Eric Ager, a Democrat. The answer is not clear.

Indeed, the individual assistance program is hard to explain “because it wasn’t designed to be the primary thing for people,” says former FEMA director Craig Fugate, who managed 87 disasters in 2011 under President Barack Obama. “When people get asked, ‘Can you pay back a loan?’ – they say, ‘I don’t want a loan. One of my family members was killed. I just lost my home. Can’t you just help me?’ Well, FEMA can help, but nothing to replace your home.”

That dynamic came to a head last month in Raleigh, the state capital, when lawmakers grilled representatives from the Governor’s Recovery Office for Western North Carolina (GROW NC), a new state agency.

When asked why FEMA emergency trailers that were provided as temporary housing were empty, Jonathan Krebs, an adviser to GROW NC, said that “Most people don’t want them.” He said that many people have, in fact, found decent and safe housing. “I don’t believe we’re being held back by FEMA,” said Mr. Krebs.

Some lawmakers took umbrage.

“The way it’s being presented is that FEMA is taking care of it, and they’re not,” responded Rep. Mark Pless, a Republican from hard-hit Haywood County, who says he knows people still struggling to find housing.

In 2019, with the dramatic rise in the number of people crossing the U.S. southern border, Congress authorized the federal government to reimburse cities that helped house unauthorized migrants as part of a new – and separate – Shelter and Services Program, which falls under the Department of Homeland Security but is run by FEMA, according to The Associated Press. That program has become a flash point for some Republicans, who incorrectly claim it’s taking money from people hit by hurricanes or floods.

A series of unfortunate events

In many ways, North Carolina is an example of a disaster-resilient state. Deep veins of self-reliance and anti-government sentiment run through these mountains. But it’s also a state that created 22 separate rebuilding programs after Hurricane Floyd in 1999, and a subsequent surge of hurricanes left parts of North Carolina in tatters.

As such, North Carolina serves as a guidepost for reforms, says Gavin Smith, who managed hurricane recovery efforts in North Carolina and Mississippi after Hurricanes Floyd and Katrina.

“States ought to take more responsibility,” says Dr. Smith, now an environmental planning professor at North Carolina State University in Raleigh. But states can’t serve up help like the phalanx of Blackhawk helicopters that the U.S. Army provided after Helene. Indeed, there was talk after the flawed response to Katrina in 2005 of abolishing FEMA.

Mr. Fugate, the former FEMA director, says that reforms should include rethinking federally funded programs that incentivize building in vulnerable areas by better assessing the economic costs. Another idea is to reward states that take steps toward resilience.

Risks and responsibilities

“We’re living in an era of unusual events,” says Professor Cutter, co-director of the Hazards Vulnerability & Resilience Institute at the University of South Carolina, in Columbia. “You do need some mechanism to force states, communities, and individuals to take more responsibility for the risks they assume.”

David Wyatt, a local farmer from Bat Cave, says wistfully that the town “ain’t ever going to be what it was.” But he’s also not ready to blame FEMA. He knows FEMA funds help pay for the state dump trucks and bulldozers rebuilding the road to neighboring Chimney Rock. That money will also pay to .

And when Mr. Wyatt raised concerns with a U.S. representative that farmers seemed left out of the recovery loop, a meeting that included FEMA representatives was quickly called to discuss farm aid.

“I made a call,” says Mr. Wyatt. “And something happened.”

Editor's note: This story, originally published on Feb. 11, has been updated to include the correct date for Hurricane Floyd, which is 1999.