In Golden State's solar boom, a tale of 'two Californias'

Loading...

| Los Angeles

The Golden State may produce more solar energy than anywhere else in the country, but when it comes to being green, there are “two Californias,” says Assemblywoman Susan Eggman.

The mountainous “spine” of central California, as Ms. Eggman likes to call it, is very different from the coast: there are more , higher electricity bills, and for solar panel installation.

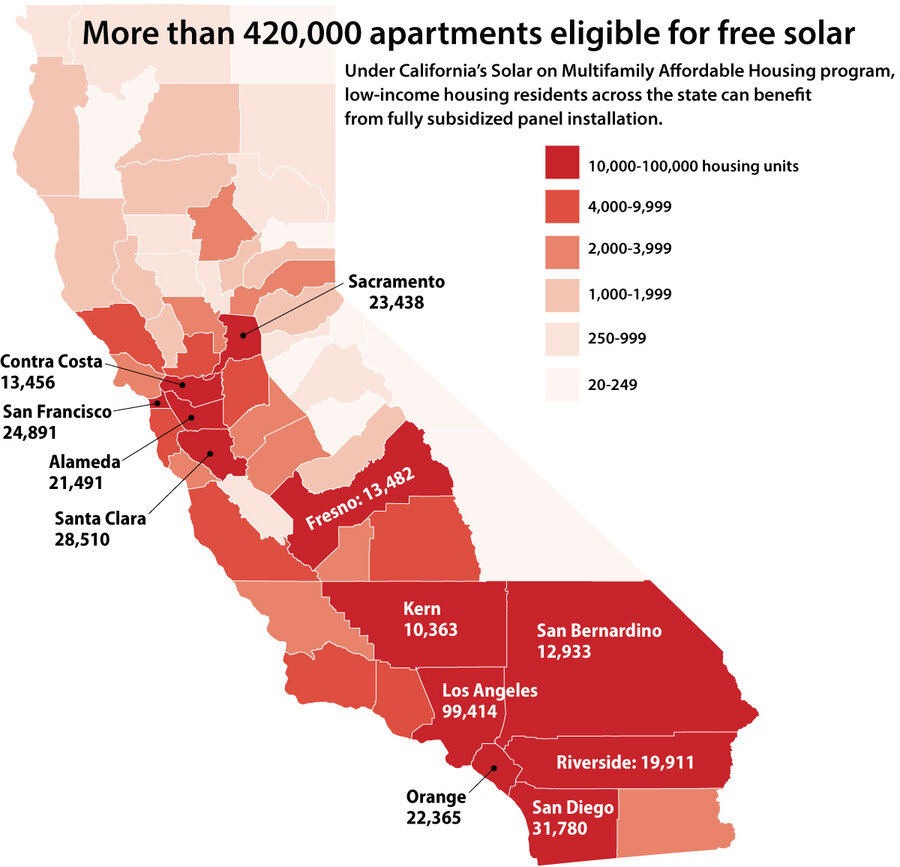

To bring California’s green reputation to places like her hometown of Stockton, Calif., Eggman created the Solar on Multifamily Affordable Housing (SOMAH) program. Under Assembly Bill 693, the program fully subsidizes solar panels on��multifamily buildings that are located in disadvantaged areas, have a number of federally subsidized units, or where the majority of tenants��earn less than�� of the area’s average income.��

“If we are going to experience a revolution in how we think about energy, it should be for everyone, not just elites,” says Eggman. “If you give people a chance, and offer them an opportunity to be a part of this, they will do it.... We just haven't done a good enough job of extending the opportunity.”

Until now, solar panels – and the savings they bring – have largely been a luxury for only wealthy, single-family homeowners. Unless low-income Californians own their own home, they don’t have the autonomy over their building to install solar panels, even if they could afford the ��installation costs. After these upfront costs, solar paneled-homeowners can get credits on their electricity bill through California’s net metering program, and even get paid for excess solar energy they produce.��

“The way energy metering is set up, it is very lucrative for people with solar systems and they are being funded by everyone else who doesn’t have solar. It’s inequitable and it’s a concern,” says Elise Torres, staff attorney at TURN, The Utility Reform Network, an advocacy group that works to protect low-income homeowners from high electricity bills. “[SOMAH] is something we could get behind and support.”

By 2030, California aims to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions��to��, a plan that includes deriving at least 50 percent of its electricity needs from renewable energy.

SOMAH presents an opportunity to meet ambitious statewide goals, says Gladys Limón, executive director of the California Environmental Justice Alliance, a nonprofit that cosponsored SOMAH. A 2012 report from the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) found that only ��was installed in disadvantaged communities, while these same communities likely make up 25 percent of the state.

“California has been a leader in setting ambitious energy goals, but we need to make sure that all communities have access ... or else we will fail,” says Ms. Limón. “There is a greater understanding [in the state legislature] of the need to make sure disadvantaged communities aren’t left behind in the clean energy economy, but there is still a lot of work to do.”

'We pick paying the bills'

The director of Esperanza Community Housing, Nancy Halpern Ibrahim, and her neighbors, many of whom are Latino, say that their local environment is too often treated as if it were disposable.

“The environmental injustice is often crassly evident [in Los Angeles],” says Ms. Ibrahim.

For years, Esperanza Community Housing has been fighting to permanently close the nearby AllenCo Energy drilling site, which community members say has contributed to various health problems. Ibrahim keeps a mason jar of oil from the AllenCo site on a bookshelf in her office to remind herself of her community’s battles.

Esperanza’s Budlong Apartments – a 12-unit apartment building located less than two miles from the AllenCo drilling site – is one of the nearly 800 buildings in Los Angeles that qualify for SOMAH benefits. And while the program does not solve all issues of environmental injustice in Los Angeles, it is a step in the right direction, says Ibrahim.

“Anything that democratizes a green benefit by prioritizing communities who can least afford it,” says Ibrahim, motioning around her, “I support.”

CPUC has tried to bring solar panels to these communities before. The Single-Family Affordable Solar Housing Program (SASH) and the Multifamily Affordable Solar Housing Program (MASH) were launched in 2009 as the country’s , offering rebates and incentives for installation.

But even for affordable housing developers, who often have more money on hand and may value an environmental reputation, installation is still too expensive with these programs.

The Community Corporation of Santa Monica (CCSM) rents to almost 4,000 low-income Californians, and about 500 of them are children, says executive director Tara Barauskas. Thus far, MASH has been the best financial deal Ms. Barauskas can find for her buildings. They have used the program to install panels on some of their complexes but it’s not always affordable – even though commitment to energy efficiency is an important component of CCSM’s mission.

“On some buildings, if we had to fix other things, we couldn’t do the solar panels,” says Barauskas. “They weren't necessary for survival.... If it's between paying the bills or solar panels, we pick paying the bills.”

Reimagining solar incentives

Although SOMAH passed the state legislature in the fall of 2015, it wasn’t until January��that CPUC agreed upon the final structure of the program. CPUC plans to hire a full-time administrator by the fall, and begin signing up housing developments for installations soon after.��

Despite some overlapping features with previous incentive programs, the latest SOMAH initiative is different. Not only are the panels fully subsidized, but the program also has another key aspect that differentiates it from its predecessors: 51 percent of the energy bill savings must go to the tenant, not the landlord or building owner.

“This is not a continuation of MASH, but a reimagining of the next 12 years of programming.... It goes beyond being an incentive program,” says Stan Greschner, vice president of government relations at GRID Alternatives, the nonprofit selected by the public utility to administer SASH.��“It really has the potential to be the most innovative and comprehensive multi-family clean energy programs in the country.”

SOMAH plans to be a bigger, both in terms of the number of Californians served and the amount of solar energy produced. Within the next 10 years, SOMAH plans to install 300 megawatts of solar panels. By comparison, the state’s MASH program has installed of energy since 2008.

At least 3,500 buildings across the state currently qualify for panel installation under SOMAH, says CPUC solar analyst Tory Francisco, and in these buildings there are almost 255,000 individual rent-assisted units.

Of course, a program of this scale is not cheap. The initiative will likely cost $100 million annually, funded by the state’s greenhouse gas cap-and-trade program. When it was going through the state legislature, of both the state Assembly and Senate opposed SOMAH. Eggman attributes the majority of this opposition to discomfort with the program’s funding source.

“If you are against cap and trade, then you need to be consistent and vote against everything that’s a part of it,” says Eggman.

But apart from some politicians, it is difficult to find an industry or activist group that opposes this legislation.

Solar companies are especially excited about SOMAH, says Kelly Knutsen, director of technology advancement at California Solar Energy Industries Association (CALSEA), because it opens up a new market with cost-efficient installation.

“It had support from the housing community, environmentalists, and not only did utility companies not oppose it, Southern California Edison actually supported it,” says Mr. Knutsen. “I’m not trying to be overly rosy about it, but it’s seen as a good use of public dollars.”

[Editor's note: This story has been updated to correct a misidentification of the utility that supported AB 693. It is Southern California Edison.]