Can 'super-corals' save the reefs?

Loading...

They should have all died. At least that’s what the worst-case-scenario predictions suggested.

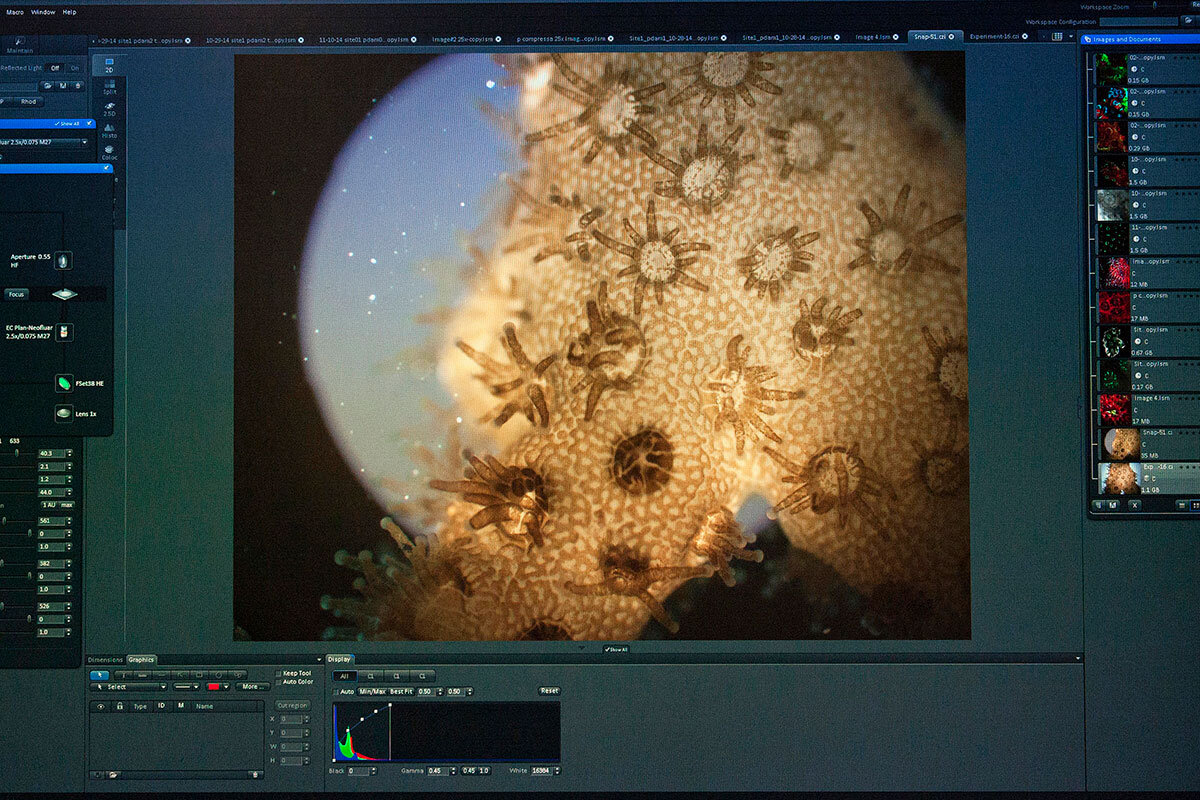

But when Andréa Grottoli peered at the corals growing in tanks on Hawaii’s Coconut Island earlier this month, she breathed a sigh of relief. Some still lived.

For the past two years, Professor Grottoli and her colleagues had subjected these corals to some truly harsh conditions, the kind that climate models suggest could become the new normal by the end of the 21st century. When she harvested them from reefs around the Hawaiian island of Oahu, Grottoli had hoped that some would acclimate to the excessively warm and acidic waters of the tank, but “there was a real risk that they were all going to die after two years,” the Ohio State University coral researcher says.

Indeed, some of the corals had bleached under their new conditions. But a couple held their characteristic color. The team still has to examine the surviving corals in the laboratory to see if and how they truly acclimated to the new conditions, but “I’m glad they didn’t all die,” Grottoli says. “I’m glad that we have survivors and we have a story of resilience.”

The apparent resilience of even a few specimens of coral offers marine biologists a hint of hope that reefs will exist long into the future, despite rapidly warming temperatures, rampant overfishing, and persistent ocean pollution. But a few surviving corals dominating a monochromatic reef isn’t the same as a thriving reef. So is it an environmental win if reefs persist but biodiversity is lost?

That’s a question that many coral reef biologists are grappling with. As it becomes increasingly evident that reefs of the future won’t continue to contain their characteristic biodiversity, scientists are forced to weigh two of their highest values, biodiversity and ecosystem resilience, against each other. But the two are also tangled together, as diversity is seen as key to long-term resilience of an ecosystem.

This tension isn’t limited to coral reef science. Ecologists across fields contemplate the same question: Is it possible to have ecosystem-wide resilience without biodiversity, and to maintain both when a system is bombarded with threats?

Super-corals to the rescue?

Coral reefs thrive on three distinct layers of diversity – and each has its own relationship to resilience. Reefs support thousands of marine organisms, from fish to marine worms to algae, and more. This splendid biodiversity is what captivates tourists and nature photographers from all over the world. There are also hundreds of distinct species of coral globally. And within each coral species there is also thought to be broad genetic diversity.

A rich diversity among any species is thought to promote overall ecosystem resilience. If one species in a diverse ecosystem is wiped out, there’s probably another species that can step in and perform the same ecological function. In the case of reefs, many coral species can build the stony structure that other animals call home. So as long as some stony corals survive, so too can reefs.

“The risk with low diversity, and this is true in any ecosystem, is that if you have disease propagate through and everything is the same species and it’s a disease that targets that species, you lose everything,” Grottoli explains. “With low diversity, you lose that ecosystem-level resilience” even if reefs still exist.

Grottoli and others are on a mission to find so-called super-corals that are particularly resilient to the extreme conditions predicted with anthropogenic climate change.

Some of these super-corals are indeed quite “super.” In one of Grottoli’s , she found some corals in the Gulf of Aqaba in the northern Red Sea that can be heated to 6 degrees C above their normal summertime temperatures before they release their symbiotic algae and bleach.

But not every population of a species is necessarily resilient. One of these super-coral species in the northern Red Sea, Pocillopora damicornis, was also one of the species that Grottoli collected in Hawaii. And the Hawaiian population died in their tanks with just 2 degrees C of warming. This distinction suggests that something might be at play on a more minute level as well: adaptation to local conditions.

The idea is that under different conditions (on opposite sides of the globe, in this case), certain traits will be favored differently within the same coral species. This can happen in a few different ways, says Robert Toonen, a coral biologist at the Hawai’i Institute of Marine Biology in Kaneohe and Grottoli’s collaborator in Hawaii.

Classic evolutionary adaptation could be at play, as genetic traits that are more advantageous in distinct environments could be selected for over a generation or two. Some scientists are also investigating whether there is some sort of epigenetic mechanism at play, with heritable changes in gene function rather than the DNA itself. Or perhaps an organism has particularly plastic traits that can be expressed differently in different environments, making it possible to adapt to a new habitat in its lifetime. Better understanding the mechanisms at play could help coral scientists better understand how well the world’s diverse reefs will survive into the next century.

Diversity plays a key role with all these mechanisms, particularly when it comes to heritable genetics.

“Genetic diversity within a species is basically fuel for adaptive evolution,” says Mikhail Matz, a coral geneticist at the University of Texas at Austin. A broad variety of genetic mutations provides more options for adaptation in the face of changing environmental pressures, he explains.

So if that genetic diversity exists, adaptation can happen quite quickly, even within a generation, thus adding resilience to the overall system.

But there’s a catch. It takes a long time to build up such diverse mutations in a population. With the extreme selection pressures of rising global temperatures, the weakly adapted organisms will be selected out quickly, leaving a smaller population made up of a significantly diminished pool of genetic diversity. This will eventually create a bottleneck of genetics, as a species or population will have less variety to draw from and will therefore be less resilient.

Dr. Matz likens it to saving money. “Right now we have accumulated some genetic currency which we can spend, but it will not last forever. The income is slow, we cannot spend it too fast,” he says. “The genetic diversity existing right now is basically buying us some time to come to our senses and stop global warming. If we don’t do this, things will eventually collapse.”

A persistent glimmer of hope

Still, some ecologists see a glimmer of hope: if some reefs survive, they’ll be able to help others regenerate, too.

A recent modeling study found that the larvae from a handful of small, healthy reefs could be carried on ocean currents to dead or dying reefs across the Great Barrier Reef.

“There is a capacity for recovery that we were unaware of,” says Peter Mumby, a leader of that study and a marine spatial ecologist at the University of Queensland in Australia.

Despite such hopeful hints, we may have to change how we think of reefs.

“All the world’s reefs aren’t going to be gone” in the next century, says John Bruno, a marine ecologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “There’ll be high-latitude reefs, there’ll be reefs in places that just don’t warm for whatever reason, but there’ll be far, far fewer than what we’ve got right now, and they’ll be different.”

As an ecosystem, whether or not you consider coral reefs resilient may be somewhat of a mindset, Toonen says. “I don’t believe that coral reefs will cease to exist,” he says. “I think that they will look very different, but I think that we will continue to see corals and something that we can call a reef.”

Whether or not you see a reef as resilient without biodiversity will depend on how you define a reef, he says. Right now, the spectacular biodiversity that reefs support make them iconic and draw large crowds of diving and snorkeling tourists. But reefs also support coastal fisheries, and the stony structure of reefs protect coastlines. A single species of stony coral, or even concrete, might still yield a similar effect in some cases, Toonen suggests.

Professor Mumby agrees. “We will have to change our expectations of what reefs do for us.”