Our reporter offers vignettes of the protesters in Portland, Oregon – where they’re from, what they want, and the values and ideals motivating them to continue now that federal agents have been withdrawn.

Why is ���Ǵ��� Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

About usAlready a subscriber? Log in

Already have a subscription? Activate it

Ready for constructive world news?

Join the Monitor community.

SubscribeMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

David Clark Scott

David Clark Scott

As the lockdowns started in March, Douglas Smith’s 4-year-old son had a request: Let’s grow a sunflower as “big as our house.”

You may already know that pandemic gardening is a thing. You know this because your neighbor keeps leaving zucchini the size of scuba tanks on your doorstep.

This past spring in the Northern Hemisphere, about the time that toilet paper became scarce, a new backyard farming movement began. It started as a hedge against food shortages. that it halted orders for a few days in April to catch up. Nurseries and garden centers are still doing a booming business. But sales have gone way beyond the apocalyptic preppers.

Gardening has emerged as the ideal break from Zoom meetings. Weeding is therapeutic. The raised bed has replaced the day spa as a source of solace and rhapsodic contentment. “I found love in my garden and I honestly never expected it to get like this, but It’s so rewarding,” first-time gardener Nyajai Ellison told ABC News in Chicago.

Meanwhile, in the village of Stanstead Abbotts, England, Mr. Smith took his son’s request to heart. He ordered sunflower seeds, and started watering – twice a day. He now has towering over his two-story house, reports SouthWest Farmer.

How big is a father’s love for his son? As big as a house.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Log in

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 7 min. read )

Interview

( 5 min. read )

In our exclusive interview with the five-term congresswoman (and possible Joe Biden running mate), Rep. Karen Bass is encouraged by the growing ranks of women in leadership roles, and offers lessons on the power of relationship-building. Part of our special 100th anniversary edition on women winning the right to vote.

( 6 min. read )

Our reporter finds an awakening among young Israelis, who have been seen as politically apathetic. Street protests are fueled by a loss of trust and a newfound desire for integrity in leadership. Is this a generational shift?

Perception Gaps

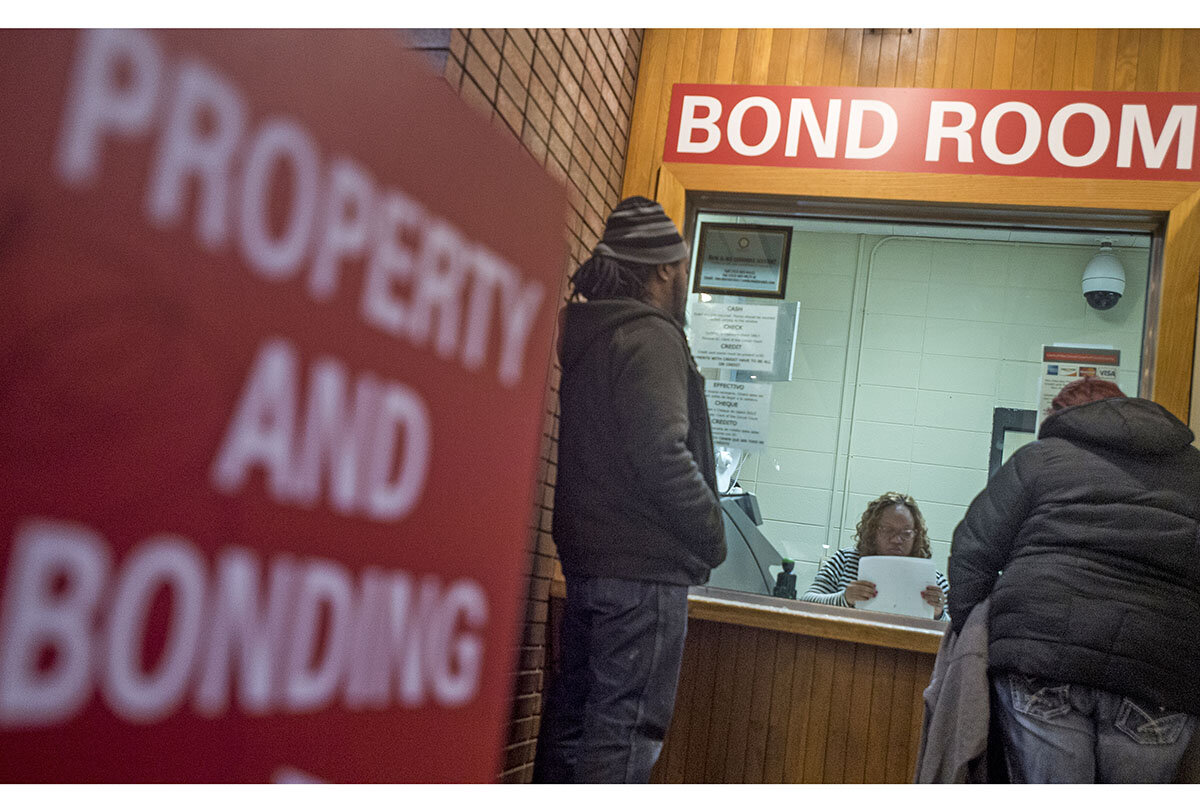

Who’s really inside America’s jails? (audio)

Did you know that most people in jail have not been convicted of a crime? Many Americans are unaware of how the criminal justice system actually works. Our new season of the “Perception Gaps” podcast sheds light on some of these misconceptions.

America Behind Bars

( 6 min. read )

Here’s another story about emerging activism. We look at how TikTok went from an apolitical app for teen dance videos to a platform for battling racism and a threat to national security, according to Trump officials.

The Monitor's View

( 3 min. read )

It’s been called the world’s largest science project, the most complex engineering feat in human history. But its enormity and intricacy aren’t even the biggest part of its story. This technology could be a solution to energy and climate problems for centuries to come.

The name of this mind-boggling effort is ITER (originally known as the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor), a megaproject that began to be assembled near Marseille, France, in August. For decades nuclear fusion has been like a genie who refuses to come out of its bottle and grant a miracle. It entices with a new way of generating electricity, a completely different approach from today’s fission-based nuclear power plants, which rely on splitting atoms. Using tremendous heat and pressure, nuclear fusion joins atoms together. While doing so, in theory at least, it would generate many times more energy than it takes to create the fusion process.

Its fuel would be largely hydrogen gas, available in abundant supply around the world. No country could corner the market on it. And compared with nuclear fission plants, fusion would produce very little in the way of radioactive materials, the tricky disposal of which is one of the great drawbacks of fission reactors.

This project deserves attention because solutions to climate change have been slow in coming. Conventional fossil fuels, including coal, are not being eliminated fast enough and scaling up renewable energy such as wind and sun has been challenging. Turning more to conventional nuclear powerplants brings not only the aforementioned disposal problems but also safety concerns, as highlighted by the disasters at Chernobyl and Fukushima.

Bernard Bigot, director-general of ITER, remains confident that his project will produce energy. But the key question is whether it will be “simple and efficient enough that it could be industrialized,” he says. “The world needs to know if this technology is available or not. Fusion could help deliver the energy supplies of the world for a very long time, maybe forever.”

The huge mechanism under construction requires the application of science and engineering at their most demanding. “Constructing the machine piece by piece will be like assembling a three-dimensional puzzle on an intricate timeline [and] with the precision of a Swiss watch,” Mr. Bigot says.

ITER is the product of an international effort that so far has survived disruption from the pandemic or from political tensions. The partners include the United States, China, India, Russia, South Korea, and members of the European Union.

It follows in the footsteps of other joint scientific endeavors such as the International Space Station (15 nations) and The Human Genome Project (20 institutions in six countries). The genome project, successfully concluded in 2003, was considered the largest collaborative biological project ever undertaken. The ITER effort, says Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, is “a perfect symbol of the age-old Indian belief ... [that] the world is one family.”

The next checkpoint should arrive in 2025 when the first plasma would be produced in the fusion process. Another decade would be needed to see if the concept works in its entirety and would be commercially viable.

The billions of dollars and years of work represent a tremendous investment. But the creativity, engineering, and sense of possibilities that fuel it will certainly help humanity find the long-term solution for its energy needs.

A ���Ǵ��� Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 3 min. read )

In these days of lockdowns and “safer-at-home” orders around the world, it can seem hard to find a sense of normalcy. But as a woman from Melbourne, Australia, has found, God-given qualities of strength, joy, and peace are a constant in our lives, there for us to feel and express even when it seems life has been turned upside down.

A message of love

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow. We’re working on a story about how some U.S. playwrights are envisioning a post-pandemic world.