A web of lawsuits involving President Trump and his associates – filed by Russian oligarchs, the Democratic Party, and a porn star, among others – may seem primarily like a source of cable news entertainment. But this civil litigation could pose grave risks to Mr. Trump and his presidency.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

Clayton Collins

Clayton Collins

It was a week of active diplomacy – and signs that more of it is needed. (On Monday we’ll look at where the sparring between Iran and Israel could lead.)

What else?

There were steps forward, some certain, some qualified. Kenya, with a boost from Japan, into space, a first for a sub-Saharan nation. California moved to on new single-family houses, which will at first hike housing costs in an already brutal market.

There were steps backward, such as racially charged events and in which better communication might have averted needless confrontation.

In another reminder that what seems like game-changing news can lead at first to a simple reset, all of the value it lost during the Cambridge Analytica privacy scandal.

But it was also a big week for the triumph of earnest opposition. In Nicaragua, protests reflected a questioning of decades of “revolutionary” rule. In Tunisia, young independents notched in elections. In Armenia, a became prime minister. In Malaysia, a 92-year-old former leader with old political foes.

Running through most of this: a perpetual testing of old limits and assumptions, a social yearning, a push-pull that rocks old patterns of thinking and keeps bringing change.

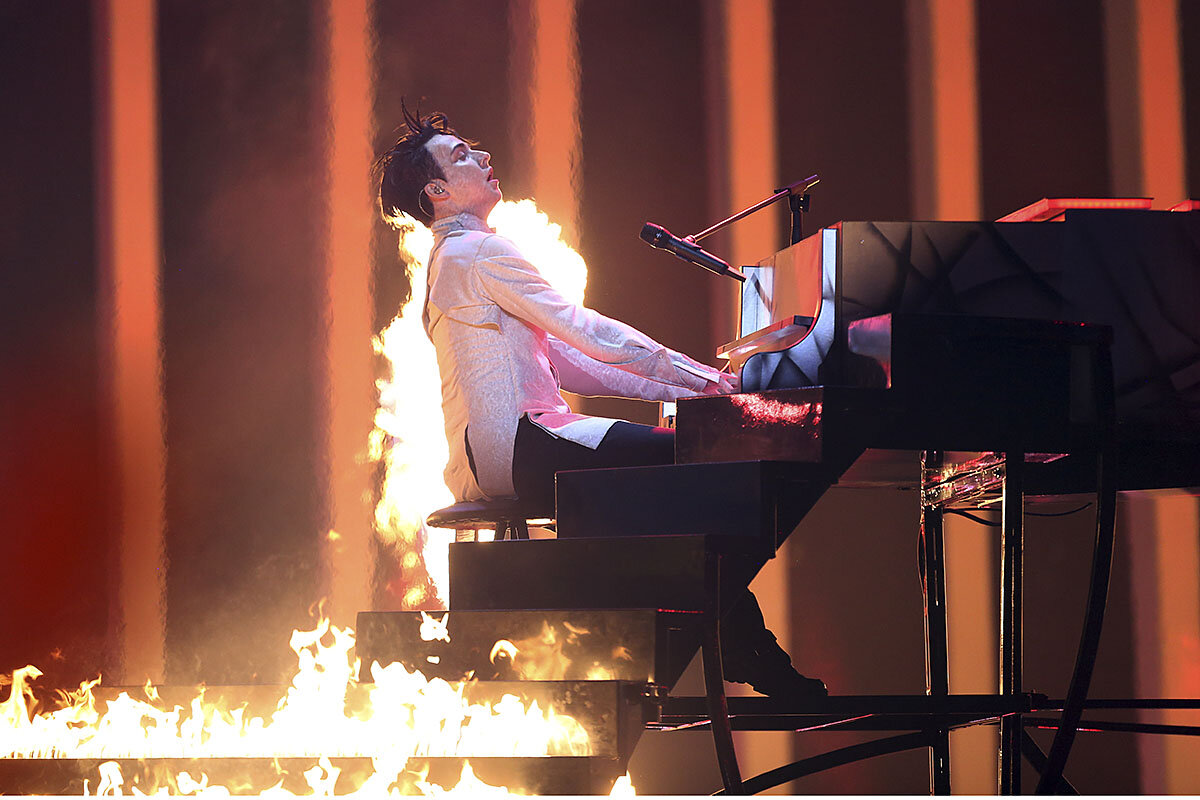

Now to our five stories for your Friday, looking at the enforcement of legal and social standards, emboldened thought in France and China, and language politics at a European song competition.