Sunday's Japanese election showed a nation worried about North Korea. But that doesn't necessarily mean it's ready to part with its deep commitment to pacifism.

Why is ���Ǵ��� Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

About usAlready a subscriber? Log in

Already have a subscription? Activate it

Ready for constructive world news?

Join the Monitor community.

SubscribeMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Does fairness flip at the US-Canadian border? Listening to the tax debates going on in both countries, one might think so. In the name of helping the “middle class,” they are considering diverging paths.

In Canada, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau wants to crack down on the tax advantages available to upper-middle-income earners. In the United States, President Trump wants to expand them.

Of course, Canada and the US have different tax structures and different administrations in charge. But there’s something deeper, too. In his book, “Dream Hoarders,” Richard Reeves argues that the real class divide in America is between the upper-middle class and everyone else. The 1 percent aren’t the issue, he says. It’s the top 20 percent who are pulling away.

And that appears to be where the US and Canada are diverging. To Mr. Trudeau, this group is part of “a privileged few.” To Mr. Trump, they’re part of “the middle class” that he says will benefit from his plan.

“Who is middle class?” How each country answers that question will define its sense of identity and prosperity.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Log in

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 5 min. read )

( 5 min. read )

The Harvey Weinstein scandal has spawned a powerful hashtag that has given other victims the strength to come forward: #MeToo. To truly address sexual crime, however, another hashtag might be just as important: #MenToo.

( 7 min. read )

The Las Vegas shootings highlighted the post-9/11 trend of entire communities – not just individuals – grappling with a sense of trauma. That means cities are increasingly thinking about residents' mental well-being, not just their physical safety.

( 6 min. read )

What happens when the last school in your town closes? It's a question facing many corners of rural America, and for some, the answer has been for the community to open its own charter school.

( 6 min. read )

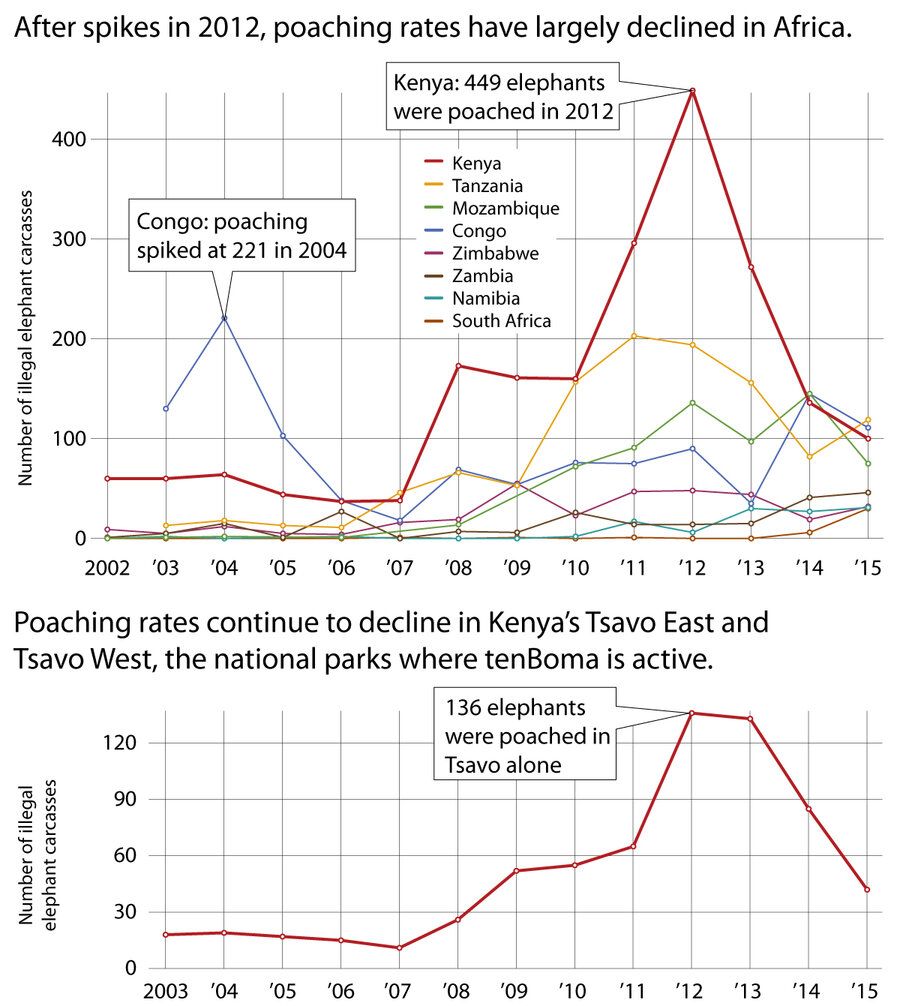

Counterterrorism, at its heart, is not about drone strikes. It is about uncovering and destroying the hidden networks that seek to hide violent purposes in plain sight. And that has made it a powerful tool for fighting poaching in Kenya.

The Monitor's View

( 2 min. read )

In a highly symbolic victory against Islamic State (ISIS) last week, the US military helped liberate the group’s de facto capital of Raqqa after a four-month battle. Once a thriving Syrian city of more than 200,000 people, however, Raqqa today has been reduced to rubble while most residents have fled. Land mines laid by ISIS and a lack of basic services have kept many people from returning.

Now the United States and its allies are asking: Can Raqqa be restored, perhaps even made into a symbol of peace in the Middle East?

Over the past year, other cities in Syria and Iraq have been retaken from ISIS. But Raqqa stands out because it was the first big city taken by the group in 2014. Its tragic plight also represents a basic issue for the region: Terrorists arise in places with a political and social vacuum. In Raqqa’s case, the vacuum was the result of a civil war in Syria between pro-democracy forces and the regime of President Bashar al-Assad since 2011.

The city is now in the hands of the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-Arab coalition. The US, Britain, Saudi Arabia, and many other countries are considering ways to stabilize Raqqa and raise money for its reconstruction. Yet finding the money may be the easy part.

To save Raqqa from both terrorists and the Assad regime, the SDF and its newly established Raqqa Civil Council must quickly establish a broad and democratic government. Residents will return if they know there is a system in place that can peacefully resolve ethnic and religious rivalries. Wars may be won by the force of arms but peace can only be kept by the force of ideals, such as freedom, respect, and equality.

The US has struggled in Afghanistan and Iraq to help establish stable, democratic government. And it has totally failed at that task in Libya. A liberated Raqqa, however, offers an opportunity to learn from past mistakes and create a model in a region beset by religious violence.

ISIS may be largely defeated as a fighting group. But its ideas of intolerance must still be countered by living examples of reconciliation between people.

A ���Ǵ��� Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 3 min. read )

“[W]ar is not inevitable,” noted a recent Monitor editorial, attributing this statement to United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres. It’s tempting to raise an eyebrow at this if we’re perusing a history book or listening to the news. But the Bible speaks of a God-given peace “like a river” (Isaiah 66:12). Rivers flow – that’s their nature. So this peace that’s “like a river” isn’t just an absence of conflict. It’s a powerful force for good that we can discern by shifting our thought away from dwelling on the discord and fear, and looking instead to a deep spiritual peace that is so powerful that it actually precludes the existence of inharmony. Even when conflict seems inescapable, being willing to let the enduring peace of divine Love lift our fear and anger is a powerful way each of us can “mobilize for peace.”

A message of love

A look ahead

Thank you for reading. Please come back tomorrow, when correspondent Dina Kraft talks to Palestinian women who are defying the traditional pressure not to openly cooperate with Israelis, and instead joining with Israeli women to call for peace.