Public debt and economic growth

Loading...

In the election of 1952 my father voted for Dwight Eisenhower. When I asked him why he explained that “FDR’s debt” was still burdening the economy — and that I and my children and my grandchildren would be paying it down for as long as we lived.Мэ

I was only six years old and had no idea what a “debt” was, let alone FDR’s. But I had nightmares about it for weeks.Мэ

Yet as the years went by my father stopped talking about “FDR’s debt,” and since I was old enough to know something about economics I never worried about it. My children have never once mentioned FDR’s debt. My four-year-old grandchild hasn’t uttered a single word about it.Мэ

By the end of World War II, the national debt was 120 percent of the entire economy. But by the mid-1950s, it was half that.Мэ

Why did it shrink? Not because the nation stopped spending. We had a Korean War, a Cold War, we rebuilt Germany and Japan, sent our GI’s to college and helped them buy homes, expanded education at all levels, and began constructing the largest public-works program in the nation’s history — the interstate highway system.

“FDR’s debt” shrank in proportion to the national economy because the national economy grew so fast.Мэ

I was reminded of this by the recent commotion over an error in aВ В by Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff.Мэ

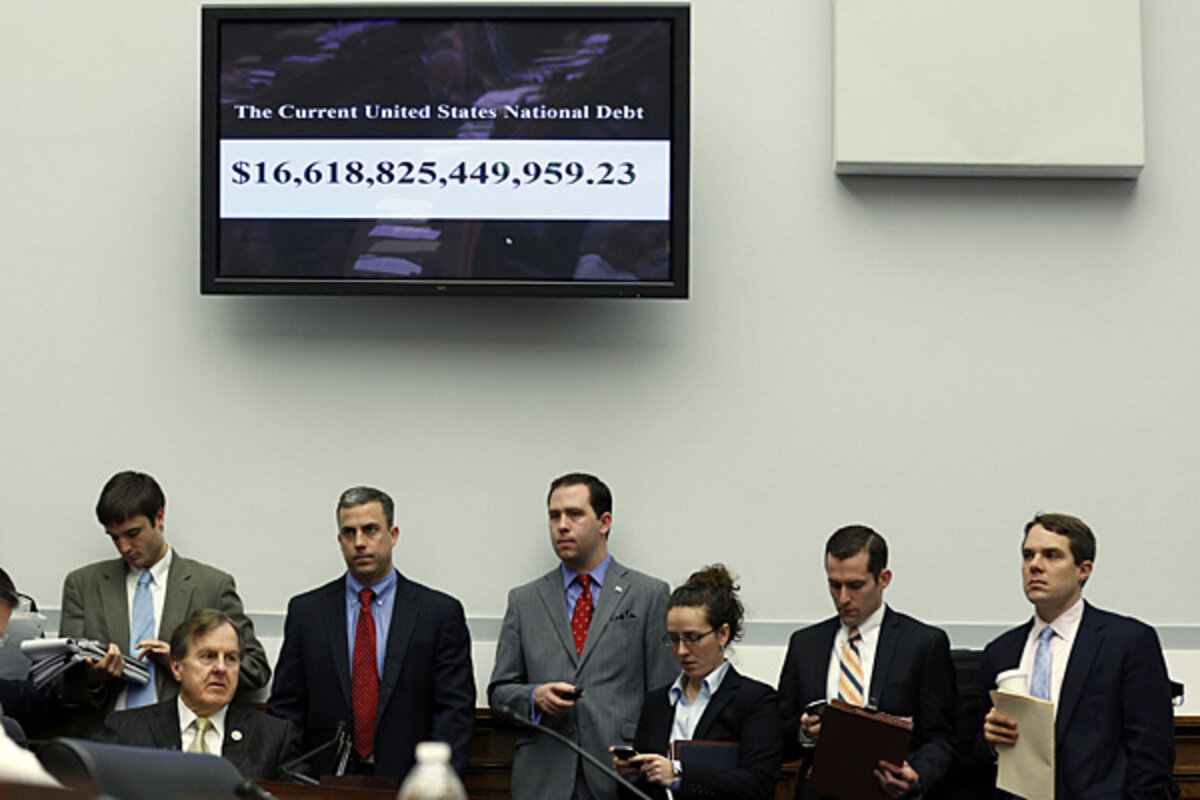

The two Harvard economists had analyzed a huge amount of data from the United States and other advanced economies linking levels of public debt to economic growth. They concluded that growth turns negative (that is, economies tend to collapse into recession) when public debt rises above 90 percent of GDP.

That finding, in turn, fueled austerics, who insisted that the budget deficit (and debt) had to be cut in order to revive economic growth.Мэ

But Reinhart and Rogoff’s computations were wrong, and average GDP growth in very-high-debt nations is around 2.2 percent rather than a negative 0.1 percent.Мэ

A few days ago, the two offered a defense in anВ В in the New York Times, asserting “very small actual differences” between their critics’ results and their own.Мэ

Regardless, Reinhart and Rogoff seem to be correct in one basic respect: Economic growth does seem to be lower in very-high-debt countries.Мэ

But the entire debate over their paper’s flaws begs the central question of cause and effect.

Is growth lower because of the high debt? That would still make the austeric’s case, even without the magic 90 percent tipping point.Мэ

Or does cause-and-effect the other way around? Maybe slow growth makes debt burdens larger. There’sВ В to suggest this is the case.Мэ

If so, government should be fueling growth through, say, spending  — at least in the short run.Мэ

As we should have learned from what happened to “FDR’s debt,” growth is the key.Мэ