How profits and resources drive foreign policy in the Trump era

Loading...

In just over a month, the Trump administration has made dramatic moves that look puzzling:

- In the midst of a growing international race to dominate the development and use of artificial intelligence, President Donald Trump reversed himself and years of U.S. national security policy last month. He allowed U.S. chipmaker Nvidia to sell its second-most powerful chips to American archrival China.

- After capturing and arresting Venezuela’s president early this month, Mr. Trump persuaded the South American nation to sell at least 30 million barrels of its oil to a U.S. fund. This fund, directed by the president, will pay for the oil and may use proceeds from its sale to repay Venezuela and subsidize investments in its deteriorated oil infrastructure.

- On Tuesday, after two days of tariff threats and counterthreats between the United States and the European Union over control of Greenland, stock markets slumped worldwide. The bellwether S&P 500 dropped more than 2% before rallying on Wednesday as the tariff threats eased.

Confused by all this? Welcome to a time of international upheaval in which a stable postwar order has dissolved, a great-power rivalry is intensifying, and alienated U.S. allies are trying to find their new place in the world.

But step back a moment, and the rules of the game become clearer: It appears that the competition among nations, especially between the U.S. and China, will rely increasingly on economic tools to achieve national goals. This strategy of leverage has a name: geo-economics.

Why We Wrote This

Responding in part to Chinese competition, President Trump is more aggressively leveraging economic tools in foreign policy, from Venezuela to Greenland.

“It seems that every day we’re reminded that we live in an era of great power rivalry, that the rules-based order is fading, that the strong can do what they can, and the weak must suffer what they must,” Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney told political and business leaders Tuesday in an unusually frank speech at their annual gathering in Davos, Switzerland. “But I also submit to you that other countries, particularly middle powers like Canada, are not powerless. They have the capacity to build a new order that embodies our values.”

Backing off threats, using new levers

Speaking on Wednesday in a 70-minute address at Davos, President Trump walked back earlier threats of military action in Greenland, saying he won’t use force. He also backed off his threat to use tariffs to gain control of the island, citing what he described as a new framework with NATO on Arctic security.

The U.S., with its enormous influence over the world’s financial system, huge market, and leading role in international institutions, has long flexed its geo-economic power. But it usually did so in consultation with allies and in the name of a greater objective, such as sanctions on Iran to fight terror financing, sanctions on Russia for its Ukraine invasion, or foundational goals such as stability, democracy, or peace.

Nations didn’t always like the moves. “People ... bristled at U.S. power, and they bristled at the idea that banks were becoming the foot soldiers, basically through sanctions, of U.S. interests,” says Abraham Newman, a professor in the government department at Georgetown University and co-author of a 2023 book, “Underground Empire: How America Weaponized the World Economy.” But “most countries agreed terrorism of the kind that happened at 9/11 was terrible, and there should be action. ... Most countries agreed you shouldn’t invade another country when you’re not under threat.”

The change today is that Mr. Trump has made his moves unilaterally and has stated America’s interests as primary rather than as something larger. And he is using these geo-economic levers of power more aggressively and frequently.

Geo-economic moves

The U.S.-China race for dominance in AI is a case in point.

The company that ultimately creates the dominant platform for advanced AI will not only make billions of dollars and offer the winning nation a potential military advantage, but might also control the network and set the rules for AI’s future use and development. That’s an enormous advantage that both Washington and Beijing hope to secure for their own tech companies.

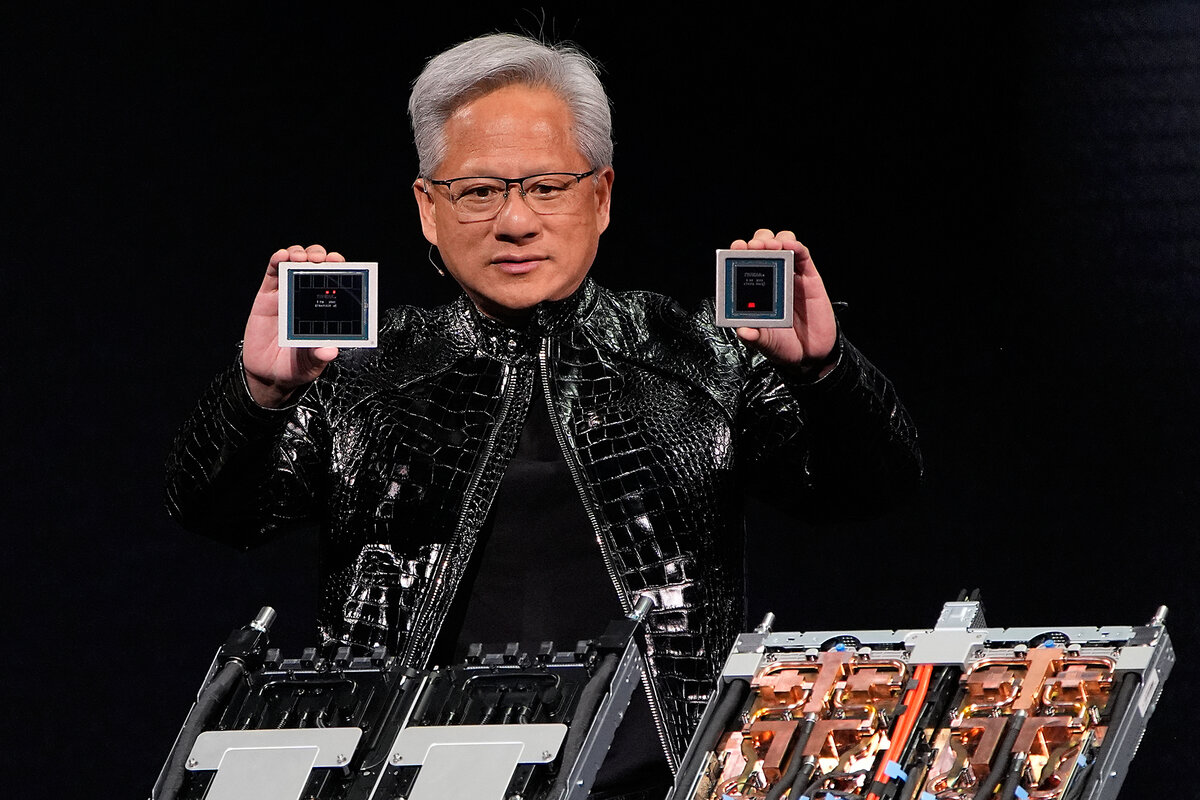

To slow China’s advances, the Biden administration banned the Asian nation’s purchase of America’s most advanced chips and other technologies – a classic Cold War tactic used against the Soviets. President Trump kept the Biden chip ban in place until this past December, when he allowed China to buy Nvidia’s second-most-powerful chip to use in its race for AI dominance.

National security experts roundly criticized the move. Some suggest the administration is trying to make the best of a bad situation, in which China’s surging economy looks unstoppable. There’s plenty “to suggest that there is a certain resignation in current U.S. foreign policy on the question of competing with China,” says Jennifer Harris, director of the Economy and Society Initiative at the Hewlett Foundation and co-author of the 2016 book “War by Other Means.”

But Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang, other tech executives, and the White House’s AI chief David Sacks reportedly made a to President Trump. By selling a chip slightly less capable than Nvidia’s latest and greatest Blackwell semiconductor, they argued, the Chinese would remain at least partially dependent on U.S. hardware. As a result, Chinese manufacturers would be less likely to grab the entire Chinese market.

That reasoning illustrates the logic of the new economic order. In geo-economics, globalization isn’t a goal. It’s a fact. In key economic areas, nations will remain interdependent. Great powers can take advantage of that if they can convince others, allies and rivals alike, to rely on their network, whether it be technological, financial, or resource-based. Dr. Newman and his co-author coined the term “weaponized interdependence” to describe this phenomenon. (Notably, China is now effectively blocking its companies from purchasing the Nvidia chips, even though access to the chips’ advanced computing power could boost its AI effort.)

After U.S. forces grabbed Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro in a daring Caracas raid, to face narcotics-related charges, previous presidents might have justified the dramatic arrest as a way to rid the world of a brutal dictator and spread democracy. Mr. Trump, by contrast, left the rest of the regime in place and refocused on economics. After some not-so-subtle military threats, he convinced leaders to redirect at least 30 million barrels of oil from China to the U.S.

The uses of Venezuelan oil

Since the world is awash with oil, the move hasn’t done much to move oil prices or to convince major U.S. oil companies to spend tens of billions to revitalize Venezuela’s dilapidated oil production infrastructure. That exercise looks too risky.

But Mr. Trump’s real prize may not be the oil itself, but depriving China of its major economic foothold in Latin America. A bonus: Cuba, another Chinese ally in the region that is heavily dependent on subsidized Venezuelan oil, must now scramble for another supplier.

“China has significant economic interests in Venezuela,” Elizabeth Economy, senior fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, pointed out in t last week. “Its oil, telecom, and mining companies are all deeply invested in the country.”

China has also tried numerous times to invest in Greenland. In the past decade, China has offered to invest in airports, an abandoned naval station, and a satellite ground station, according to a by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. In 2018, it announced an Arctic policy that’s come to be known as the “Polar Silk Road.” So far, “its ambitions have been largely stalled and curtailed by U.S. and Danish stakeholders,” as well as by opposition from Denmark, which controls the foreign affairs and defense of the huge island, the .

The prize is ostensibly Greenland’s two large deposits of rare earth minerals, which have been identified but not developed. The minerals are key to some essential military, tech, and auto applications.

Leveraging rare earth minerals

Last year, China used its dominant control of rare earth processing to convince Mr. Trump to lower his punishing tariffs. That’s another geo-economic tool: using choke points within an economic network or supply chain to pressure other nations. The president appears eager to mitigate that vulnerability, even though developing Greenland’s rare earth deposits would be expensive.

One can paint a picture of a shrewd leader, using the latest tools to counter a geopolitical rival. Many national security experts and economists disagree. Just because Mr. Trump has used geo-economic tools to counter Beijing doesn’t mean that he’s used them effectively or strategically, economists say. Instead of working with Denmark to further restrict Chinese access to mineral deposits and pave the way for potential rare earth mining, President Trump has angered the Scandinavian country and its European allies. The broad-based tariffs Mr. Trump has imposed on dozens of nations have also undermined efforts to work with allies to counter China.

“Everybody wants to see this as, it’s about great-power politics. [Or] it’s about something that they’re very familiar with,” says Dr. Newman of Georgetown.

In his view, one big motivator is control of the money in these deals. In the case of chip sales to China, Nvidia has agreed to pay 10% of its revenue to the U.S. government. In the case of Venezuela, oil sales to the U.S. will go to a special fund controlled by Mr. Trump.

“Also,” he adds, “it’s about status, about saying, ‘I’m the dominant player.’”