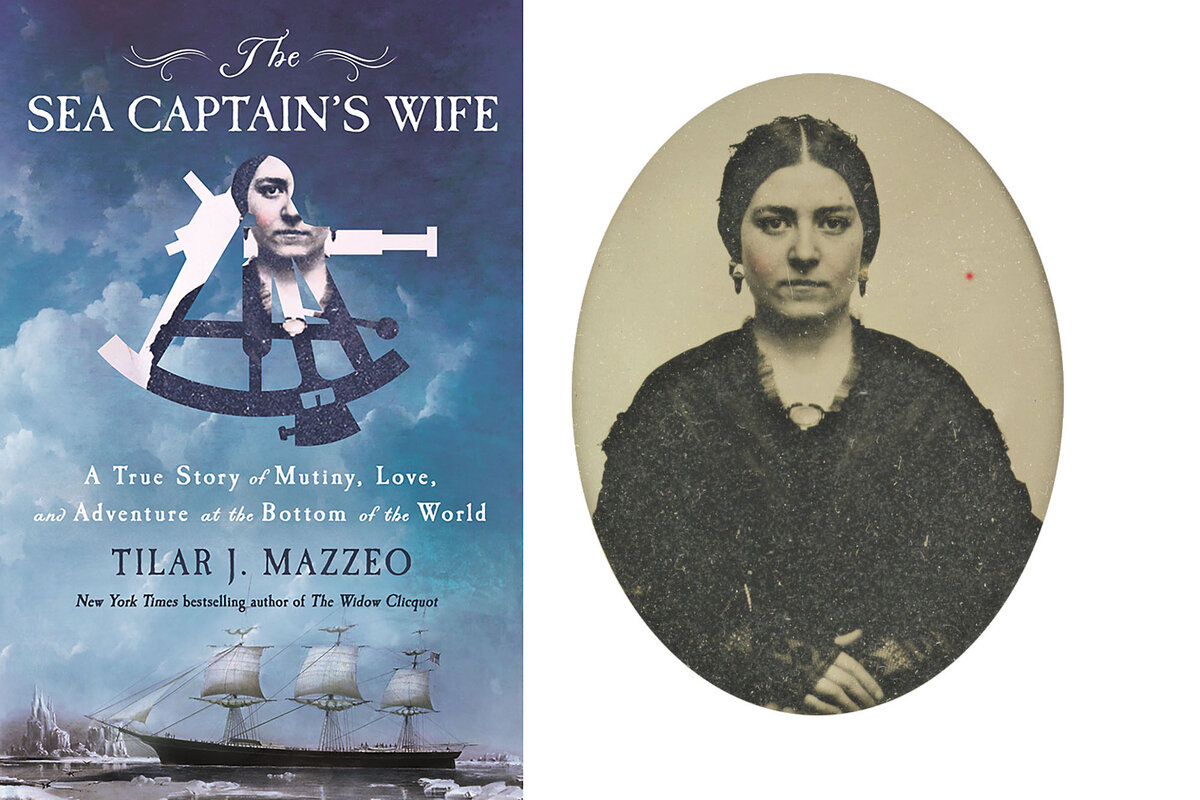

When the captain’s wife took charge: The true story of Mary Ann Patten

Loading...

Before the transatlantic telegraph cable, the transcontinental railroad, and the advent of flight, most of the world’s business was conducted by ship – and captaining ships was a man’s business. Women rarely traveled on the fast-moving sailing ships, known as clippers, that powered the 19th-century global economy. A clipper captain transporting cargo might agree to carry passengers, and women were occasionally among them. In addition, a captain might be accompanied by his wife.

If a wife were aboard the ship, Tilar J. Mazzeo explains in her gripping book, “The Sea Captain’s Wife,” she was allowed only in the staterooms and on the vessel’s quarterdeck; she was permitted to speak only to her husband, their steward, the ship’s first mate, and any passengers on board. This context helps explain how extraordinary a position 19-year-old Mary Ann Patten was in when, in 1856, her husband, Captain Joshua Patten, fell ill as their ship was headed for Drake’s Passage, the perilous body of water between South America and Antarctica.

The book tells the story, well-known in its time, of how she took command of the vessel, becoming the first woman to captain a merchant clipper.

Why We Wrote This

Women on board 19th-century clipper ships were not always welcome. But when the captain of Neptune’s Car fell ill, the skill and savvy of his 19-year-old wife, who was also pregnant at the time, brought the voyage to a safe conclusion.

Mary Ann had previously accompanied Joshua on the same ship, Neptune’s Car, on a 15-month circumnavigation of the world. The newlyweds, young and in love, didn’t want to be separated. (When they married in 1853, Joshua was 25 and Mary Ann was just 15.) The trip’s first leg, from New York to San Francisco, required sailing around the southernmost tip of South America; the Panama Canal, which greatly shortened the route, wouldn’t open until 1914. From California they traveled to Hong Kong and Britain before returning to America.

Joshua had worked at sea since he was a teenager. Mary Ann grew up impoverished in Boston, but, unusual for a girl of her social class, she had learned to read and write and do basic mathematics. On that first circumnavigation, Mazzeo writes, “she passed the long hours looking up calculations in the nautical almanac and scribbling sums in pencil on a bit of paper until she had mastered the art of celestial navigation.” When several crew members were injured while repairing a broken mast, Mary Ann, consulting the ship’s medical books, nursed them to health. These experiences would serve her well on the calamitous 1856 voyage when Joshua, feverish and delirious, was unable to captain the vessel.

Mazzeo, a historian and an experienced sailor herself, deftly explains the mechanics of the impressive clippers, which commonly measured 200 feet from bow to stern and contained up to 10,000 square feet of canvas sail. The author also effectively conveys the cultural position of the clipper captains, whom she calls ‚Äúthe rock stars and elite athletes of the mid-nineteenth century.‚Äù Captains were well-compensated for their dangerous work ‚Äì shipwrecks were not unexceptional ‚Äì and they received bonuses for speedy arrivals at port. They also participated in lucrative races with other clipper captains, which garnered widespread newspaper coverage and were wagered on by the public.¬Ý

A few successful circumnavigations could secure a captain’s financial future. This was the Pattens’ hope – what the author calls “a simple and lovely dream” – as they set out on their second extended voyage together in 1856. If Joshua earned enough money to retire early, they would build a waterfront farm in his native Maine.

Mazzeo’s narrative slowly builds toward an action-packed climax. (One quibble is that it perhaps builds too slowly: We are well into the book’s second half by the time we reach the heart of the drama.) Joshua, before becoming incapacitated, has placed the treacherous and mutinous first mate of Neptune’s Car below deck, in shackles. The second mate is illiterate and thus unable to navigate the ship. On Sept. 5, 1856, Mary Ann, who has discovered during the journey that she is pregnant, asks the crew to accept her as their captain.

The men, many of whom are aware of her keen navigational skills and some of whom are veterans of the previous voyage, during which she cared for the injured, cheer and call out “Captain Patten.” “The younger seamen later recounted how the old salts among them had tears in their eyes,” Mazzeo writes. From there, Mary Ann leads Neptune’s Car around Cape Horn through an 18-day gale before arriving, two months later, in San Francisco.

Word of Mary Ann‚Äôs heroics spread in California and then across America and throughout the world. Newspapers breathlessly reported her story. She was the subject of an epic poem, and ‚ÄúUncle Tom‚Äôs Cabin‚Äù author Harriet Beecher Stowe paid tribute to her in writing. ‚ÄúIt is difficult to overstate ... the fame of Mary Ann Patten in the late 1850s and into the 1860s,‚Äù Mazzeo writes.¬Ý

That fame couldn‚Äôt protect Mary Ann from tragedies that continued to befall her upon her return home. But it at least ensured that she would be remembered among mariners. Mazzeo reports that a building at the United States Merchant Marine Academy is named after her and that cadets there still learn about her achievement. Now, thanks to Mazzeo, that reach can be extended to history buffs and, indeed, to anyone who enjoys a good sea story.¬Ý