When Belle ├ēpoque Paris absorbed Russian ├®migr├®s fleeing revolution

Loading...

Lost amid the horrors of war inflicted on the people of Ukraine since the Feb. 24 invasion have been the stories of Russian citizens fleeing their own country, fearing the effects of international sanctions and worsening autocracy. These refugees often come from RussiaŌĆÖs skilled and educated classes, and their situation echoes events from a century ago, when large numbers of Russians were displaced by the fall of the Romanov dynasty and the upheaval of the October Revolution.

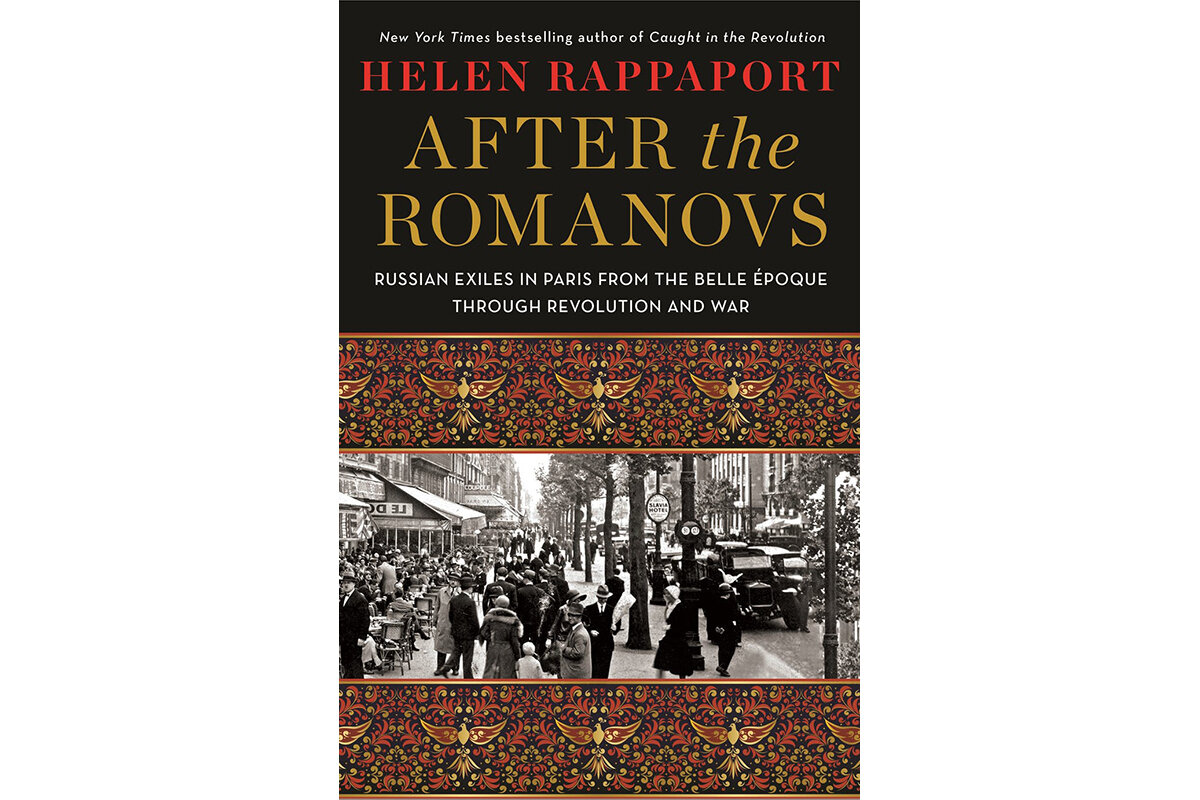

What became of that wave of immigrants who flocked to Paris by the tens of thousands in 1917? How did these refugees ŌĆō many of whom were from RussiaŌĆÖs monied and propertied elite and some of whom had been among the artistic, literary, and intellectual stars of that now-vanished world ŌĆō adapt to life in France? These are the central questions explored in ŌĆ£After the Romanovs: Russian Exiles in Paris from the Belle ├ēpoque Through Revolution and WarŌĆØ by historian Helen Rappaport.

France was already well known to the Russian elite, who vacationed in Paris, often spending their seemingly bottomless wealth with abandon, usually becoming the favorite topic of gossip in the cityŌĆÖs salons and restaurants. ŌĆ£Everywhere in Paris,ŌĆØ Rappaport writes, ŌĆ£the tills of the exclusive parfumiers, furriers, fine art dealers, and antiques emporiums rang to lavish amounts of Russian money.ŌĆØ┬Ā

But when the old Russian world broke apart, when Tsar Nicholas II and his family were murdered as revolution convulsed the country, all those Russian grand dukes, duchesses, and other members of the aristocracy suddenly had to scramble and improvise for their very survival. Naturally, many hundreds of them fled to the city theyŌĆÖd known in happier times. Now they found themselves thrown upon old haunts like the Maison Russe or Sainte-Genevieve-des-Bois, this time as needy supplicants instead of big spenders.

Rappaport presents masterful portraits of these refugees, many of whom were in the same position. As Rappaport notes, they had no idea how to handle money; ŌĆ£the Russian aristocracy had never carried cash or written checks; they had left that to their minions to deal with.ŌĆØ One former princess spoke for her set when she commented, ŌĆ£for you see, I had always had everything.ŌĆØ┬Ā

The pages of RappaportŌĆÖs book are wonderfully populated with exiles ŌĆō from titled nobility such as Grand Duke Dmitri Pavolich, one of many Romanovs who made it out of Russia alive, to the anonymous women who embroidered garments for fashion designer Coco Chanel. Among the artists who fled the revolution was dance genius Sergey Diaghilev, leader of the Ballets Russes. There was ŌĆ£MotherŌĆØ Maria Skobtsova, who survived the Russian Revolution, eked out a living in Paris serving the needy, only to end up in the Ravensbr├╝ck concentration camp during World War II, where she died just days before it was liberated by the advancing Russian troops.┬Ā

Among the authors who escaped to France was Ivan Bunin, ŌĆ£revered as a leading voice of the Russian intelligentsia and a master of the short story in the tradition of Anton Chekhov.ŌĆØ He and his partner Vera Muromtseva, like many of their fellow exiles, noticed the surge of immigration happening around them. ŌĆ£I like Paris,ŌĆØ Muromtseva wrote in her diary in 1920, ŌĆ£but IŌĆÖve hardly seen anything here except other Russians.ŌĆØ┬Ā

Even though circumstances forced these Russians to adapt to ordinary French life (stories abounded of former princes driving taxicabs), most of them aggressively resisted assimilation. And this had the side effect of invigorating the city and its arts. ŌĆ£All of this new intake flocking to Paris shared a passionate desire to protect and preserve their culture and their sense of Russianness ŌĆō and the inspiration in art, music, and literature that sprang from it,ŌĆØ Rappaport writes. ŌĆ£This new injection of talent revitalized the ├®migr├® community of Paris, bolstering it with a sense of mission to preserve their heritage at all costs.ŌĆØ┬Ā

Readers familiar with earlier Rappaport books like ŌĆ£The Last Days of the RomanovsŌĆØ or ŌĆ£The Romanov SistersŌĆØ will know to expect the subtle and fluid genius that runs through her latest. Rappaport not only crafts a lovingly detailed picture of the City of Light (as Gertrude Stein put it, ŌĆ£Paris was where the twentieth century wasŌĆØ), she also fills its parks and caf├®s and boulevards with an amazing cast of characters. Those dukes and princesses and writers and artists, in all their desperate struggles and passionate adaptations, come alive again in these pages.