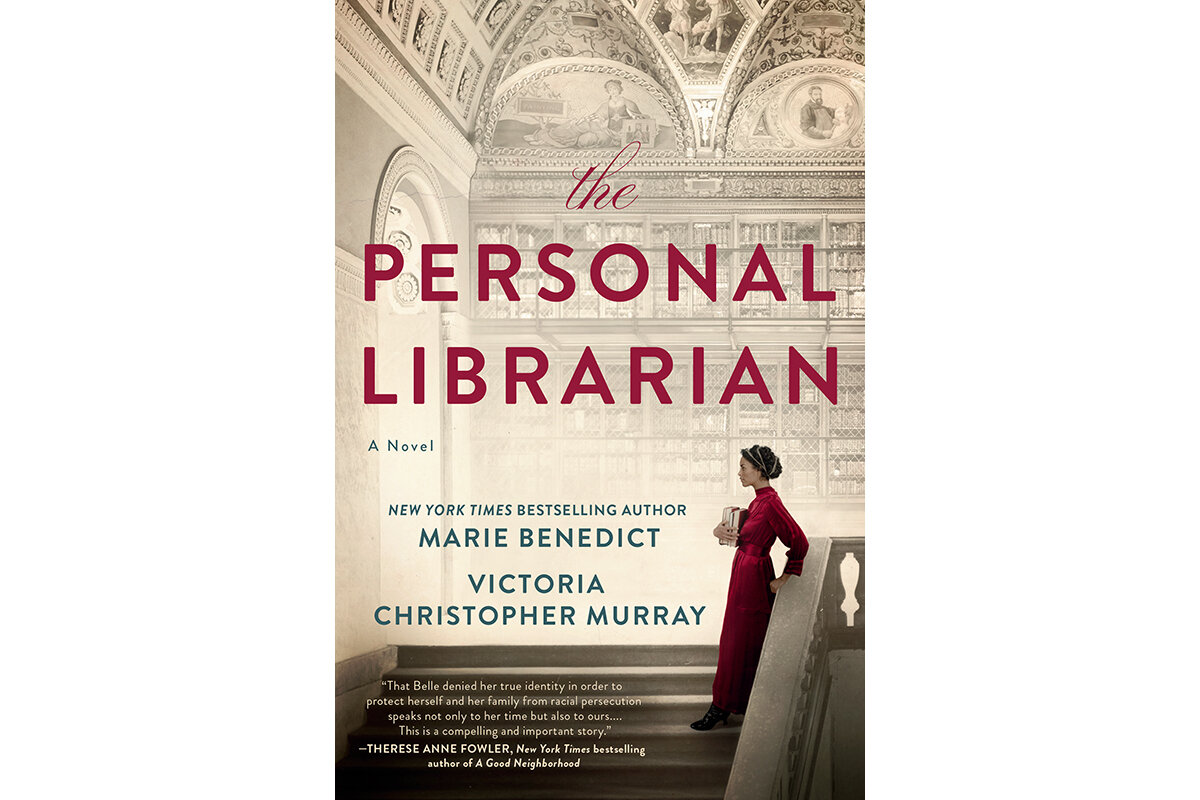

J.P. Morgan’s librarian hid her race. A novel imagines the toll on her.

Loading...

Some books leave you wondering why the author has chosen to tell this particular story, and why now. This is emphatically not the case with ‚ÄúThe Personal Librarian,‚Äù a novel about the woman who helped shape the Morgan Library‚Äôs spectacular collection of rare books and art more than a century ago. It quickly becomes clear why two popular authors, Marie Benedict and Victoria Christopher Murray, have teamed up to tell this important, inspirational story.¬Ý

Belle da Costa Greene‚Äôs success in the almost exclusively male world of art and rare book dealers was an unusual feat for a woman in the early 20th century. But what makes it even more extraordinary ‚Äì and such rich material for historical fiction ‚Äì is the secret she harbored throughout her long career:¬ÝShe hailed from a prominent, light-skinned Black family, many of whose members had chosen to pass as white.¬Ý

‚ÄúThe Personal Librarian‚Äù reminds readers that this decision was not made lightly. After the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the Civil Rights Act in 1883 ‚Äì a ruling that ushered in Jim Crow segregation and gave¬Ýwhite supremacy and racial¬Ýdiscrimination¬Ýlegal cover,¬Ýthe¬Ýramifications¬Ýof which¬Ýare felt to this day ‚Äì few¬Ýopportunities were open to anyone classified as nonwhite.

Why We Wrote This

How much would you be willing to sacrifice in order to advance? At the turn of the 20th century, some Black people chose to “pass” as white in a bid to circumvent racism and segregation.

For Greene’s pragmatic mother, Genevieve Fleet Greener, passing as white became the best option to enhance her children’s prospects in an increasingly segregated, racist America – even though it meant breaking ties with her close-knit family in Washington. Worse, it meant estrangement from her husband, Richard Greener – a professor of law and prominent advocate for civil rights who was the first Black graduate of Harvard University. Although often mistaken for a white man, he believed that all Black people should unite to fight against prejudice rather than “trying to cross the color line.”

To explain her olive complexion, ‚Äúda Costa‚Äù was added to Greene‚Äôs altered surname to represent an invented Portuguese grandmother. She was still in her 20s when J. Pierpont Morgan ‚Äì imposing business magnate, passionate bibliophile, and known philanderer ‚Äì hired her away from Princeton University‚Äôs rare books collection in 1905 to curate his new library in Manhattan.¬Ý

Told from Greene‚Äôs perspective, ‚ÄúThe Personal Librarian‚Äù deftly conveys her deep knowledge of medieval illuminated manuscripts, her skill in handling her mercurial, overbearing boss, and her prowess in navigating the rarefied circles of art dealers and Gilded Age society. But the book never loses sight of the cost incurred by her family secret through all these professional triumphs.¬Ý

Stories about racial passing have long been fixtures of American literature, including Nella Larsen’s novel “Passing” (1929), Philip Roth’s “The Human Stain” (2000), and Brit Bennett’s “The Vanishing Half” (2020). These books, along with Bliss Broyard’s memoir, “One Drop” (2007) – which grew from her discovery that her father, literary critic Anatole Broyard, had a hidden multiracial history – underscore the high stakes for people who dare to cross the color line. More importantly, they highlight both the outrage and absurdity of racial prejudice.

The authors of ‚ÄúThe Personal Librarian‚Äù make it clear that many Black people like Greene and her family owe their light skin to¬Ýthe sexual violence inflicted on enslaved Black women by white men.¬ÝYet¬Ýlater in life,¬Ýand despite past and present¬Ýtrauma, their¬Ýtenacious, accomplished heroine assesses her remarkable career, declaring, ‚ÄúI presented proof of the heights that colored folks could fly if untethered from racist bindings.‚Äù¬Ý

In this telling, even Greene’s father, the author of a prescient essay titled “The White Problem,” comes to respect the “life of meaning” his daughter has forged for herself. But he also holds out hope for a better future when he says, “One day, Belle, we will be able to reach back through the decades and claim you as one of our own.”

And here we are, in 2021, a year after George Floyd’s murder and the ensuing outrage and Black Lives Matter demonstrations it provoked, reading about the true heritage of J.P. Morgan’s personal librarian.

The backstory behind “The Personal Librarian” adds another intriguing dimension. Historical novelist Benedict, whose previous subjects include Lady Clementine Churchill and Hedy Lamarr, learned about Greene many years ago from a docent in the Morgan Library. But she felt she needed a collaborator, particularly for the Black perspective. She chose Victoria Christopher Murray, author of a fiction series, “The Seven Deadly Sins,” as well as “Stand Your Ground,” a sensitive contemporary novel about the shooting of a Black teenager by a white police officer. In an author’s note, Murray writes that her own light-skinned grandmother occasionally passed as white.

Their teamwork has yielded an engrossing, well-researched read, which the authors assure us is anchored in “the available facts.” Liberties have, of course, been taken, and it’s mostly in these imagined scenes of high drama – such as the physical tension between Greene and her possessive, much older boss – that the writing often feels overheated.

The prose turns positively purple when it comes to Greene’s affair with art historian Bernard Berenson, a Lithuanian-born Jew who passed himself off as a Boston Brahmin. (He does not come across well.) Air and voices grow “thick with emotion” to connote sexual desire. Other, smaller stumbling blocks include anachronistic expressions like “it came with the territory,” “I feel seen,” and “compartmentalizing my sadness.”

That said, Greene is an inspiring, compelling heroine. Although she has been written about before ‚Äì most notably in Heidi Ardizzone‚Äôs biography, ‚ÄúAn Illuminated Life: Belle Da Costa Greene‚Äôs Journey from Prejudice to Privilege‚Äù (2007) ‚Äì one hopes that ‚ÄúThe Personal Librarian‚Äù will introduce her story to a wider audience.¬Ý

In addition to the Monitor, Heller McAlpin reviews books regularly for NPR, The Wall Street Journal, and the Los Angeles Times.