The Enlightenment stressed not only reason, but also empathy

Loading...

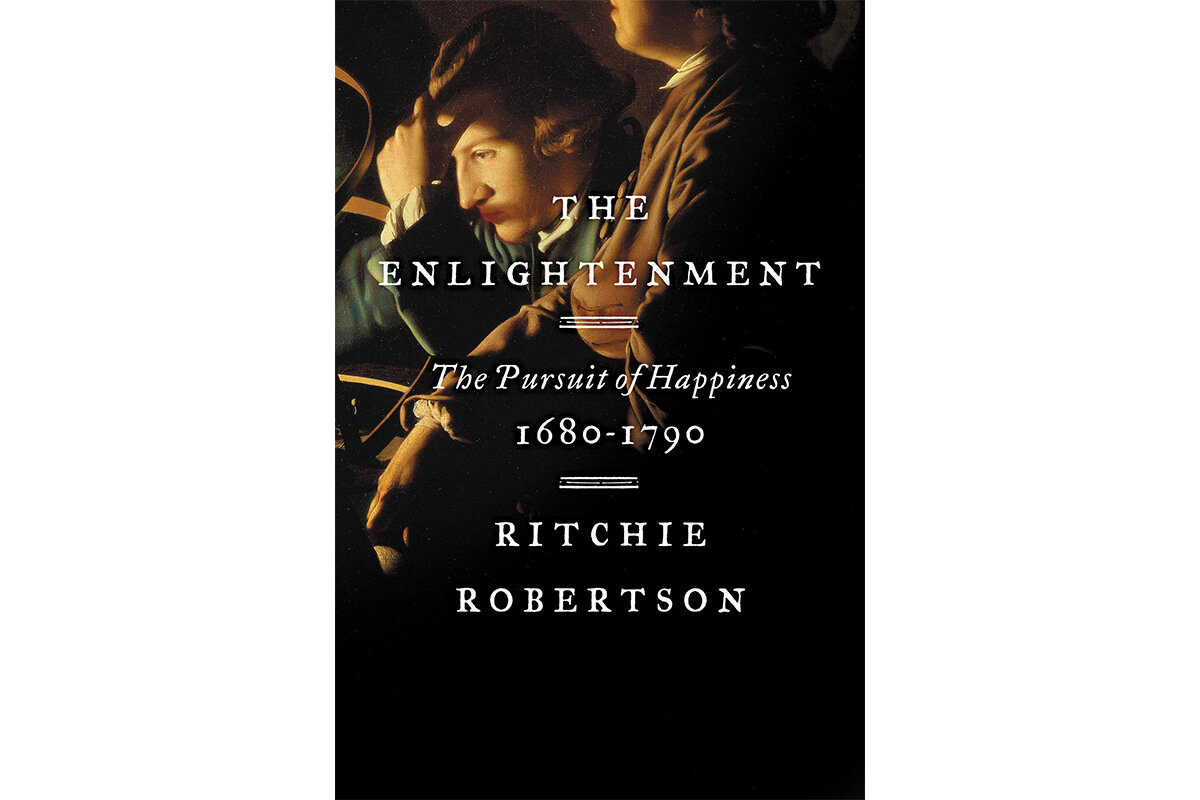

At the start of his deeply impressive new book, “The Enlightenment: The Pursuit of Happiness, 1680-1790,” University of Oxford history professor Ritchie Robertson refers to something the late Eric Hobsbawm wrote 30 years ago, describing the Enlightenment as “the only foundation for all the aspirations to build societies fit for all human beings to live in anywhere on this earth, and for the assertion and defense of their human rights as persons.”

If you’re detecting a slight note of defensiveness in Hobsbawm’s comment, you’re not mistaken. Even in his own day, Hobsbawm could sense lurking objections to the basic ideas of the Enlightenment – the great outpouring of reason, empiricism, and egalitarian values that kicked off in the late 17th century. Over the course of a century and more, the intellectual forces of the Enlightenment flooded Europe and beyond, challenging assumptions and broadening humanist perspectives. These challenges prompted resistance, and as Robertson goes about the task of telling a sweeping, bracingly eloquent narrative of what’s considered the “long 18th century,” he’s consistently addressing the misunderstandings that give rise to that resistance.

The Enlightenment, which Robertson calls a “sea change in sensibility,” had deep roots in the Scientific Revolution of the 17th century, but even so, the world’s ideologies were comfortably fixed as the story opens. Monarchies are the rule rather than the exception, species are viewed as divinely created and immutable, education is all but unknown for the general populace, and organized religions hold a social and moral power that had been growing steadily for a thousand years.

The essential dramatic appeal of the Enlightenment is how suddenly it took hold – almost overnight, it often seems. Isaac Newton’s “Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica” appeared in 1687 and is typically seen as an easy signpost of the Enlightenment’s beginning. (Robertson looks also to John Locke’s 1689 “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding.”) The key in all cases is a pronounced change in the very fundamentals of thinking.

Robertson quotes Immanuel Kant’s famous rallying call, “Have the courage to use your own intellect!” But he stresses the inaccuracy of putting all the emphasis on the “intellect” part and none on the “courage” part. “Enlightenment reason is not calculation but argument; it is pursued not by solitary thinkers armed with slide-rules, but by groups whose members often differ in their views and who meet in the settings of Enlightenment sociability,” he writes. “Reason is only one of the Enlightenment’s core attributes, alongside the passions sentiment and empathy.”

The whole spectrum of those passions is marvelously represented in these pages (which, charmingly, are illustrated throughout with the frontispieces of seminal Enlightenment works, rather than tired stereotypical paintings of Catherine the Great’s drawing room and such). Robertson has written a big, enthusiastic book about other books, from Locke’s “Two Treatises of Government,” the primer of empiricism, to David Hume’s 1739 “A Treatise of Human Nature,” about which Robertson writes: “If any philosophical work can convey to lay readers some of the excitement of doing philosophy, this surely can.” And of course he spends time with Denis Diderot and his great “Encyclopédie,” which caused controversy from the appearance of its first volumes in 1751, described here quite rightly as a landmark in the “demystification of knowledge.”

Robertson notes that thinkers of the Romantic era “denounced the Enlightenment in retrospect as the apotheosis of hyper-rational calculation.” And he argues that those denunciations have unjustly continued ever since, whether through the social criticism of Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno (which Robertson characterizes as products of misunderstandings of Enlightenment philosophy) or in elaborations by later writers like Isaiah Berlin (which Robertson attributes to a skewed understanding of an unreliable source). “The appeal of pessimism,” Robertson writes by way of summation, “lies not least in the pleasing sense of superiority it confers on its proponents.”

“The Enlightenment” ends as it begins: with a detailed rationalization that the Enlightenment ideals – liberty, personal fulfillment, scientific understanding of the world, empathy, the dethroning of dogma – are in constant need of defending against the revanchist forces that seek to empower the few through the ignorance of the many. At the moment of the book’s appearance, Robertson notes, liberal ideals are under threat in some of the very places where they were first championed.

Diderot and his fellow valiant thinkers might not have liked the idea that reason, sympathy, and equality are so constantly vulnerable – but they’d have applauded such a big and optimistic book as this.