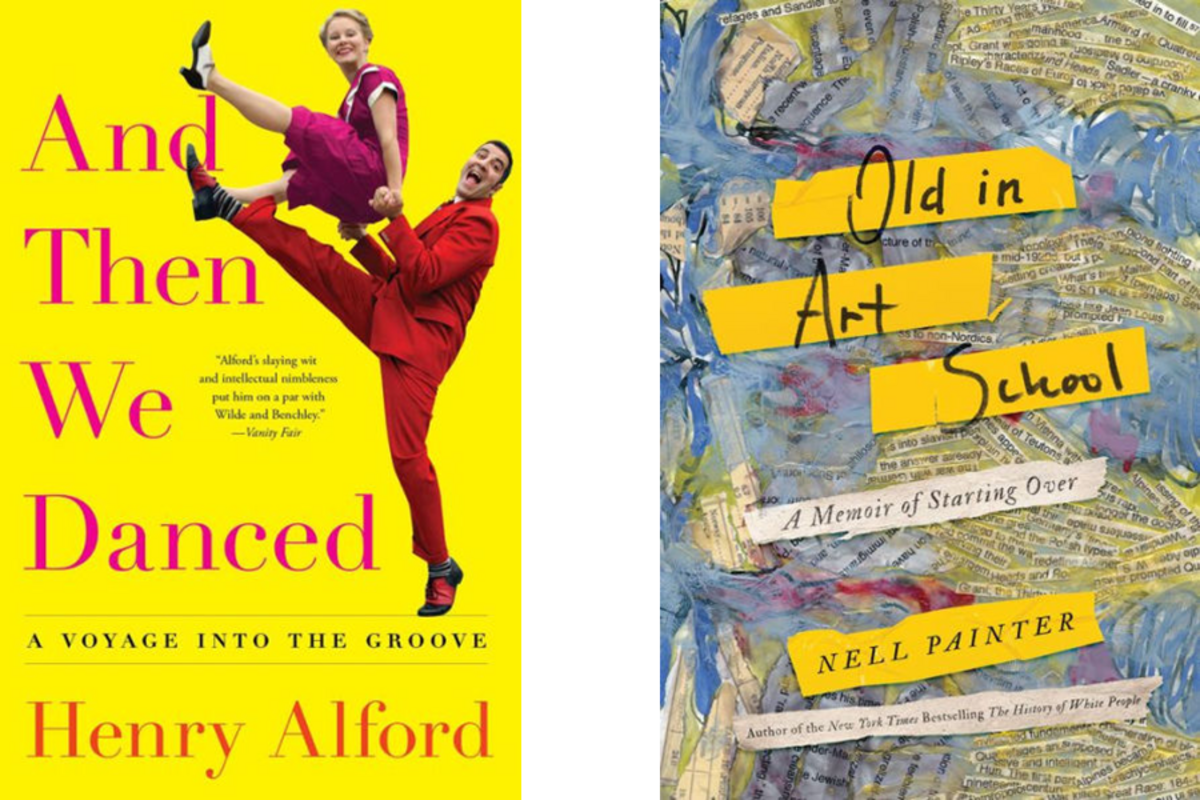

'And Then We Danced,' 'Old in Art School,' tell of later-in-life creative endeavors

Loading...

In the witty and touching And Then We Danced, journalist and humorist Henry Alford’s exploration of the world of dance, the author observes “a blatant manifestation of snobbery” in that world: the habit of referring to nonprofessional dancers simply as “non-dancers.” Nell Painter encounters her fair share of snobbery, too, as the distinguished historian retires from academia to pursue undergraduate and graduate degrees in painting, an endeavor she describes in her fascinating but fraught memoir, Old in Art School. The most hurtful instance is being told by a teacher that even if she succeeds in showing and selling her work, she will never be an artist.

Age is front and center in both books. Painter commences her undergraduate study at Rutgers’ Mason Gross School of the Arts at 64 and goes on to earn a master’s degree at the prestigious Rhode Island School of Design. While Alford begins a serious pursuit of dance at the comparatively youthful age of 50, he jokes that 50 “in gay years is 350.” Dance, of course, is more physically demanding than painting, and Alford ends up throwing his back out three times over a four-month period, necessitating repeated visits to the chiropractor, acupuncturist, and massage therapist. Painter’s injuries, meanwhile, are primarily to her ego.

“And Then We Danced,” whose author is a past winner of the Thurber Prize for American humor, is a breezy, enjoyable read. Alford, who specializes in participatory journalism, was asked to take Zumba classes and write about the then-burgeoning craze for the New York Times in 2011. Long after the story was filed, he was still taking Zumba, and from there he began broadening his dance repertoire. His current passion is contact improv.

Alford structures the book by examining different functions of dance, as related, for example, to rebellion, to emotion, to nostalgia, to healing. In most cases, he notes, whether the style is ballet, hip-hop, ballroom, or swing, whether the participants are seasoned pros or, as he writes about movingly, a group of Alzheimer’s patients, dance is “a narrative about physical intimacy – the politics and consolations thereof.”

In his youth, Alford’s limited experience with dance was tied to a gradual acceptance of his sexuality. Now, in his mid-50s, he confesses that he dances in part “to stave off the ravages of time.” He writes, “I tend to think of myself as being perpetually thirty-one years old: seasoned enough not to commit the atrocities of adolescence and my early twenties, but not so old as to have cut off any of my options in life.”

��

He would likely find Painter’s dedication to art inspirational, even if the experience itself, as described in “Old in Art School,” was often disheartening. As an African-American woman who was educated at Harvard and was a professor at Princeton, Painter notes that she’s accustomed to feeling out of place in certain settings because of her race or her gender. But her return to school marked the first time she felt out of place because of her age.��

Painter felt not only old, but, worse yet, outdated. She brought to art school a cherished belief in education and hard work, only to be given the message that true artists are born, not made. “I was such an old fuddy-duddy among the frolicking youth,” she writes, “a twentieth-century relic, a repository of useless knowledge, of experience no longer interesting, a fogy wanting art to be artful.”

That the diligence that was an asset throughout her academic career was viewed almost as a liability in art school is an intriguing tension; so too is Painter’s struggle to see art absent of the ideological analysis characteristic of her academic training. “How to disentangle the visual from the social and economic?” she asks. Unfortunately, the book gets bogged down in her bitter conflicts with her RISD teachers and classmates; these accounts start to feel more like score-settling than like necessary propellers of the narrative.

Painter was a lonely outsider at RISD, and her experience there can be painful to read about. The program turned the eminent historian “into a pathetic, insecure little stump” – this despite the fact that her final work as an historian, 2010’s sweeping "The History of White People," was at the same time being published to great acclaim. At the often brutal group critiques known as “crits,” she felt her artwork��was misunderstood or ignored.��(Reproductions of her drawings and multimedia collages appear throughout the book.) She was excluded from a group photo of her eight-person cohort; she was the only one of the eight to graduate without honors.��

“I would have quit school, burned the goddam place down, and slit my wrists,” she writes, “but there was no giving RISD the satisfaction of defeating me.”

It didn’t: Painter, at 75, continues to paint, and that’s where the book’s greatest lesson lies. “I do keep at it,” she avows, “in the pleasure of the process of making the art only I can make.”