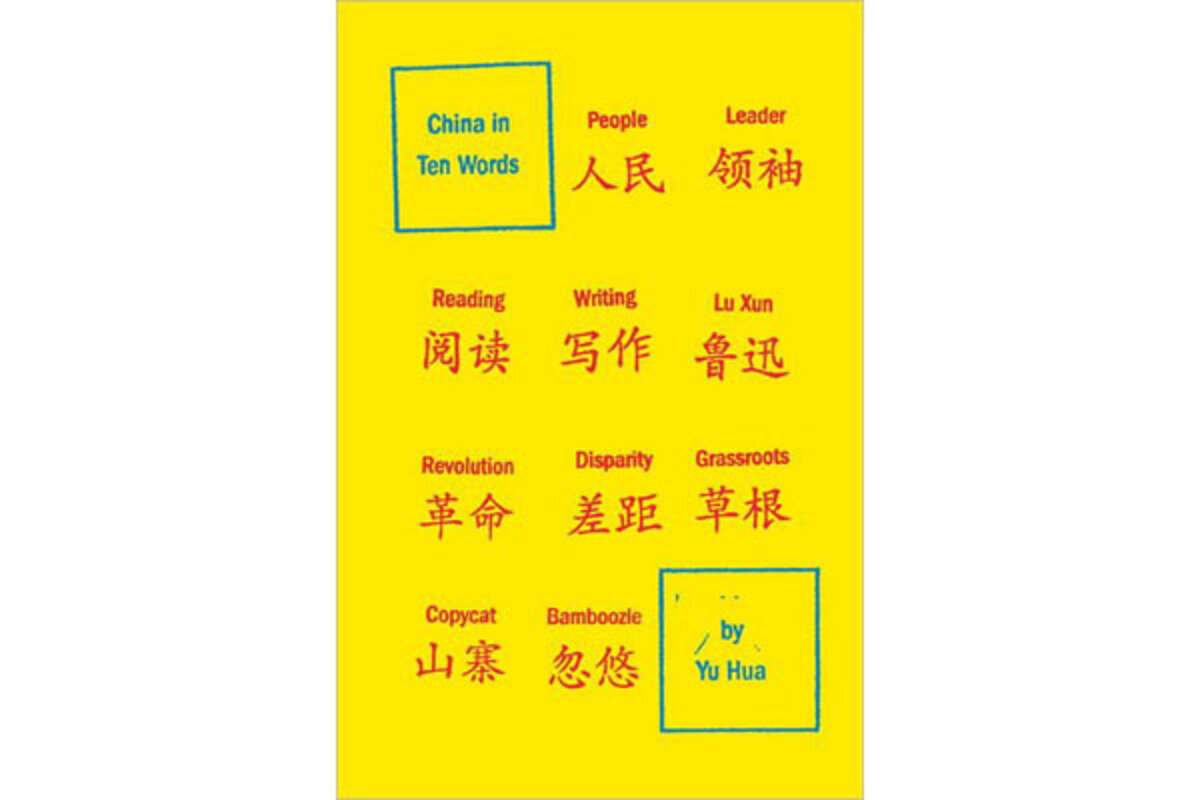

China In Ten Words

Loading...

Yu Hua is a grand master of subversion. Just as his title – China In Ten Words – promises, Yu “compress[es] the endless chatter of China today into ten simple words ... to finally clear a path through the social complexities and staggering contrasts of contemporary China.” Through laconic reduction, Yu exposes a China far beyond current Western assumptions based on adoptable baby girls, fears about Chinese überstudents out-performing America’s own, and the looming US-to-China foreign debt.

Yu is well known for his internationally award-winning novels – including “To Live” (which became a lush Zhang Yimou film), “Chronicle of a Blood Merchant,” and “Brothers” – but “China in Ten Words” is his first nonfiction work in English translation.

Here, he combines history, sociopolitical analysis, economic observations, with his own personal experiences to illustrate for readers the contrast between the deprivation that defined the Cultural Revolution of his youth and the extravagance of contemporary China.

Yu begins almost nostalgically with “the first words [he] mastered”: “the people.” During Mao’s rule, “the people” projected power and gravitas, from Mao’s directive to “‘serve the people,’” to the People’s Republic of China, to the country’s most important newspaper, People’s Daily. Three decades later, Yu muses, “I can’t think of another expression in the modern Chinese language that is such an anomaly – ubiquitous yet somehow invisible.” In a new China “where money is king,” ‘the people’ have been “denuded of meaning by Chinese realities.”

Yet even more than ‘the people,’ “the word that has lost the most value the fastest during the last thirty years ... would surely have to be ‘leader,’” Yu’s word #2. “Many years after the 1976 death of a genuine leader” – Chairman Mao – today’s Chinese are in the midst of cutthroat competition for mere survival: “the strong prey on the weak, people enrich themselves through brute force and deception, and the meek and humble suffer while the bold and unscrupulous flourish.”

Yu balances such vehemence with three chapters of personal reflection on “reading” (word #3), “writing” (word #4), and “Lu Xun” (word #5). In “reading,” Yu recalls the oppressive scarcity of books during the Cultural Revolution only to have books become worth less than wastepaper three decades later.

In “writing,” he shares some of his own literary history, from his early career as a small-town dentist to his aspirations toward “a loafer’s life in the cultural center” as a writer; he laughs off the critical praise he eventually receives for his “plain narrative language” as little more than the result of his untrained, limited vocabulary.

Yu confesses to his youthful disrespect toward China’s most influential 20th-century prose writer, Lu Xun, who was revered then reduced to a mere “catchphrase.” As a mature, acclaimed author himself, Yu is finally able to recognize and reclaim Lu Xun’s literary potency.

Continuing on through the second half of his 10 words, Yu’s sharp gaze proves unrelenting. He traces the evolving violence of “revolution” (word #6) over a span of 30 years, and examines the resulting “disparity” (word #7) between those who absconded with ill-gotten luxuries and those who remain trapped in “desolate ruins.” He captures the ruthless determination of “grassroots” (word #8) citizens, “who have nothing to lose, since they began with nothing at all,” who don’t allow concerns about morality or legality to obstruct their unwavering path toward financial gains.

When such ends seem to justify any means – methods employed can be described by words such as “copycat” (#9) and “bamboozle” (#10) – then “Harvard Communications” can use President Obama to sell their “Blockberry Whirlwind 9500,” and the penthouse allegedly leased by Bill Gates during the Beijing Olympics will “convert an obscure housing development into an apartment complex famous all over the country.”

Chapter by chapter, word by word, Yu drolly pulls off the proverbial white gloves, exposing one finger at a time until the guilty hands are stripped bare. Unblinking, Yu muses at the “you-can’t-make-this-stuff-up” reality that is today’s China: “Here, where everything is tinged with the mysterious logic of absurdist fiction, Kafka or Borges might feel quite at home.” As a consummate author, Yu contemplates “writ[ing] such a story myself. Bamboozletown might be its title.”

Terry Hong writes , a book review blog for the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Program.

Join the Monitor's book discussion on and .