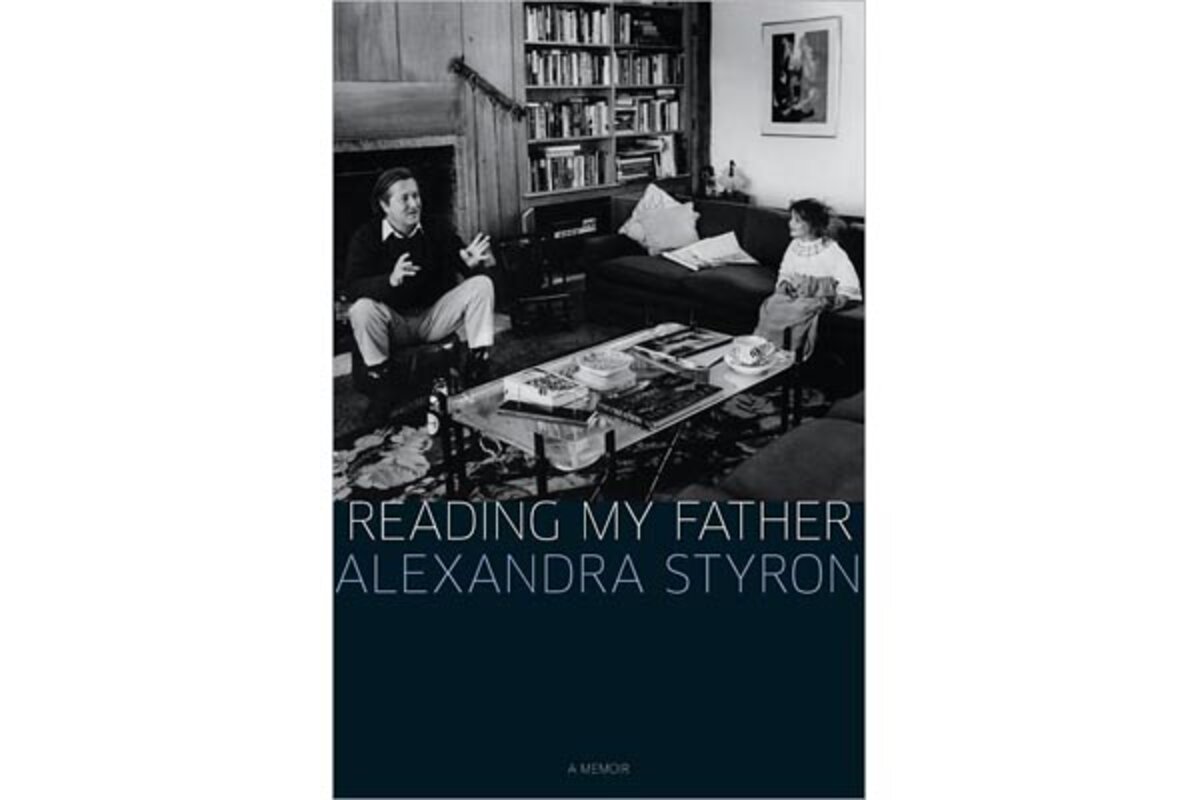

Reading My Father

Loading...

It’s almost always a mistake to learn too much about the artist you admire.

Think Picasso is a genius? Don’t ask how he treated Françoise Gilot. Believe in John Lennon as an idealistic peacemonger? Stay away from accounts of his dealings with Paul McCartney.

And so, in that spirit, I advise you to approach Reading My Father, Alexandra Styron’s candid, bruising memoir about her father, William Stryon, with caution. If you consider Styron one of the great literary voices of the 20th century, nothing in his daughter’s book will change your mind. But you may find it harder to reverence his novels quite as highly after learning of the price that Styron – and those closest to him – paid for their creation.

Pulitzer Prize 2011: Who are the winners in the arts?

Otherwise, however, “Reading My Father,” has much to recommend it. Styron is a truly gifted writer in her own right. And she has access to her father – his papers, her memories, family lore – that few others can deliver. Her book is both an informed (albeit dark) examination of a significant literary figure and an engaging (albeit poignant) memoir about growing up in the shadow of fame.

William Styron, of course, has already told the world much about his own inner darkness. In addition to his three highly acclaimed novels (“Lie Down in Darkness” in 1951; “The Confessions of Nat Turner” in 1967; and “Sophie’s Choice” in 1979), Styron was also the author of “Darkness Visible,” a 1990 nonfiction account detailing his horrific battle with depression.

But Alexandra, Styron’s youngest child of four, has issues of her own to hash out.

Who was this man? “At times querulous and taciturn, cutting and remote, melancholy when he was sober and rageful when in his cups, he inspired fear and loathing in us a good deal more often than it feels comfortable to admit.” That’s how Styron remembers her father’s domestic side. While his colleagues recall a friend and critic who was “patient, thoughtful, and enormously generous,” she feels stuck with the memory of a man who entertained himself by telling his little daughter that he was going to sell her pony to a glue factory and by suggesting that the “imbeciles” in a nearby state institution might escape and “do vile things” to her.

Styron never really succeeds in solving the mystery that was her father. She traces him from his lonely Southern boyhood (his mother died young and his stepmother openly disdained him), on through his early career struggles (when it was his own adoring father who kept him afloat), to his years of great success (she was 12 when “Sophie’s Choice” was published) and then, sadly – on to the breakdowns in 1985 and 2000 that finally incapacitated him.

She offers interesting insights into the affections and experiences that helped to shape him, including his great love for his father, his disaffection with the South and its attitudes, and his all-consuming need to prove himself as a novelist.

But she remains puzzled as to the cause of his worst anguish. “Did my father’s depression steal his creative gift?” she wonders. “Or was it the other way around, an estrangement from his muse driving him down in increments till he hit rock bottom? There’s no single answer, no simple trajectory.”

Her own unhappiness seems more clear-cut. “[W]hat I’d grown up knowing,” she writes, was “a father always at home upsetting the applecart and a mother who took every opportunity to run away.”

As for growing up among the rich and famous, she paints an often appealing picture of an affluent, “haute bohemian” household accustomed to Christmas piano parties at Leonard Bernstein’s and spontaneous summer visits from Ted Kennedy. But, she notes, eventually there was a price to be paid for all those easy childhood pleasures. As a young woman she beat herself up trying to find a talent that would ensure her an enduring place in the world of the famous. She landed in thrice-weekly therapy and even as she walked home from those sessions in tears, she recalls wryly, “I kept running into acquaintances who just had to tell me how ‘Darkness Visible’ had changed their lives.”

“Reading My Father” is not a vengeful book. Styron clearly loved her father very much. Rather than angry, she more often comes across as puzzled at the hand dealt her as the daughter of a “genius.”

“Your father was a real writer, a real artist,” his best friend tells her.” If you have to indulge somebody like that, you do.”

Styron herself is clearly not convinced. “Maybe,” she writes. “Or maybe not. Having been born into the system, how would I ever know?”

Marjorie Kehe is the Monitor’s book editor.

Join the Monitor's book discussion on and .

Shakespeare quiz: Can you match the quote to the play?