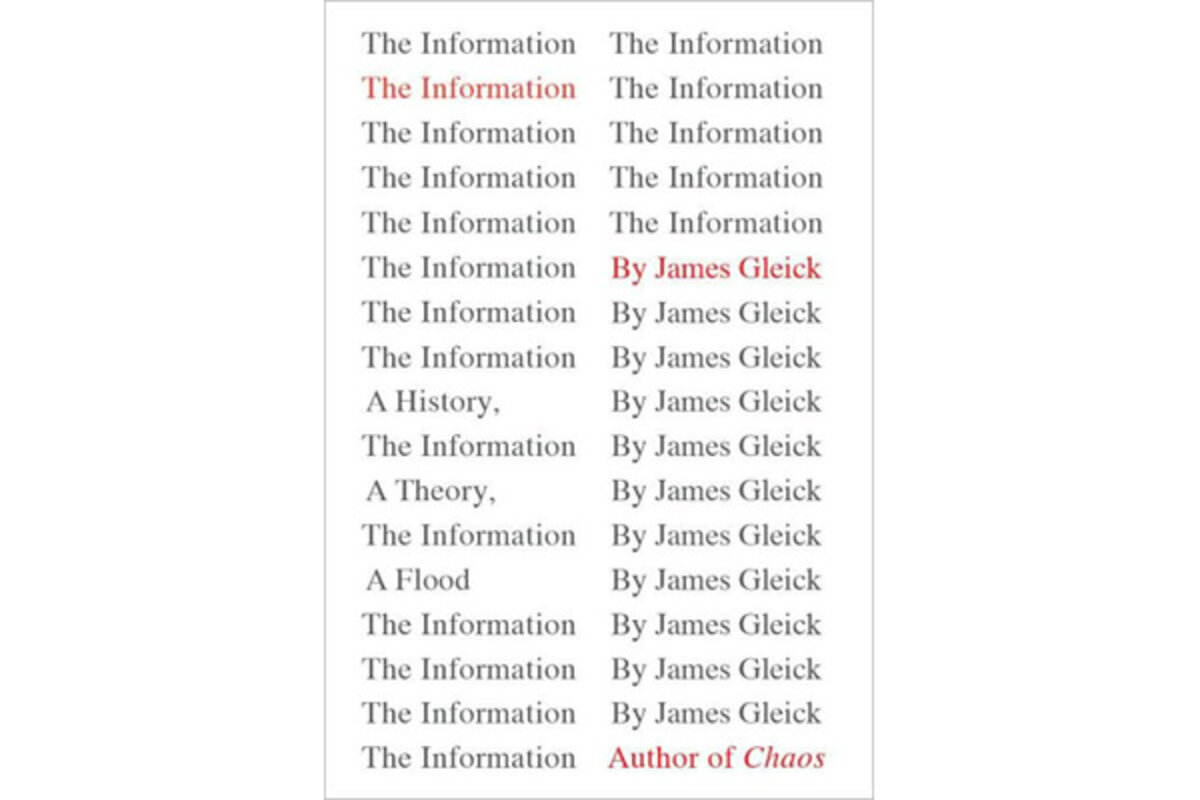

The Information: A History, A Theory, A Flood

Loading...

āThe past folds accordion-like into the present,ā James Gleick writes in The Information: A History, A Theory, A Flood, his sweeping survey of how humans use information and how this practice, in turn, has shaped humanity. Gleickās book defies easy summary, but its most abiding insight is, in fact, its reminder that the so-called āInformation Ageā of the present has deep historical parallels dating back to the dawn of time.

Gleick concludes that information, now seen as the currency of the modern world, has always been the animating force of the planet, though in ways we have only recently begun to understand.

āWe can now see that information is what our world runs on: the blood and the fuel, the vital principle,ā he tells readers. āIt pervades the sciences from top to bottom, transforming every branch of knowledge.... Now even biology has become an information science, a subject of messages, instructions, and code. Genes encapsulate information and enable procedures for reading it in and writing it out. Life spreads by networking. The body itself is an information processor.

9 books Bill Gates thinks you should read

Memory resides not just in brains but in every cell.... DNA is the quintessential information molecule, the most advanced message processor at the cellular level ā an alphabet and a code, 6 billion bits to form a human being.ā

The idea of the bit as a fundamental building block of information came from Claude Shannon, the man behind the theory of the bookās subtitle. Gleick credits Shannon with creating the conceptual framework that allowed todayās information economy to emerge.

Gleickās treatment of Shannon is the most technically challenging part of the book. E.B. White once warned that analyzing humor was like dissecting a frog, leaving one with an array of parts that seemed only dimly related to the subject. Gleickās narrative sometimes feels equally reductionist, particularly in the passages about Shannon, but āThe Informationā isnāt always or even usually concerned with dry empiricism.

Thereās sheer pleasure in these pages, too, with many chapters resembling a Victorian curio cabinet, an intimate universe of items that have lively and unlikely connections. Gleick, who approvingly describes his hero Shannon as someone who āgathered threads like a magpie,ā proves quite a magpie himself, crafting a story that includes not only Aeschylus but AT&T, as well as Beethoven and Bell Labs, Darwin and domain names, āThe Iliad,ā the telephone, and āThe Great Soviet Encyclopedia.ā

And although he deals with what can seem like grimly mechanical formulations of information theory, Gleick is also alert to the human touch. In an opening chapter on the use of African drums to communicate across vast differences, for example, he notes that drummers aspired to something more richly complicated than the bare transmission of facts. Instead of simply saying āCome back home,ā drummers would tap out a poetic exhortation:

āMake your feet come back the way they went,/ make your legs come back the way they went,/ plant your feet and legs below,/ in the village which belongs to us.ā

Gleickās study of drums sets the stage for a continuing theme of the book ā namely, the way that information history has been a point of intersection for science and the humanities. He notes the senior Oliver Wendell Holmesās 19th-century skepticism about the prospect of mechanical calculating machines, asserting that they could be nothing more than a āsatireā of human intelligence. Think of it as an earlier version of the recent debate inspired by a computerās victory on the game show āJeopardy!.ā

In his final chapters addressing contemporary information overload, Gleick reminds readers that here, too, thereās not much new under the sun.

In 1621, reports Gleick, the Oxford scholar Robert Burton complained that in the wake of the printing press, there was simply too much news and literature to keep up with. Here, again, is Gleick: āAs the printing press, the telegraph, the typewriter, the telephone, the radio, the computer, and the Internet prospered, each in its turn, people said, as if for the first time, that a burden had been placed on human communication: new complexity, new detachment, and a frightening new excess.ā

Gleickās book has been described as āambitious,ā an earnest compliment that, in publishing circles, is often synonymous with back-breaking heft and ponderous pronouncement.

āThe Informationā is a long read, and as Gleick himself concedes, āWhen information is cheap, attention becomes expensive.ā

But as Gleick also points out, āinformation is not knowledge, and knowledge is not wisdom.ā

The information glut endures, but wisdom like Gleickās is harder to come by. That alone makes āThe Informationā worth the effort.

10 most frequently challenged books of 2010

Danny Heitman, a columnist for The Baton Rouge Advocate, is the author of āA Summer of Birds: John James Audubon at Oakley House.ā

Join the Monitor's book discussion on and .