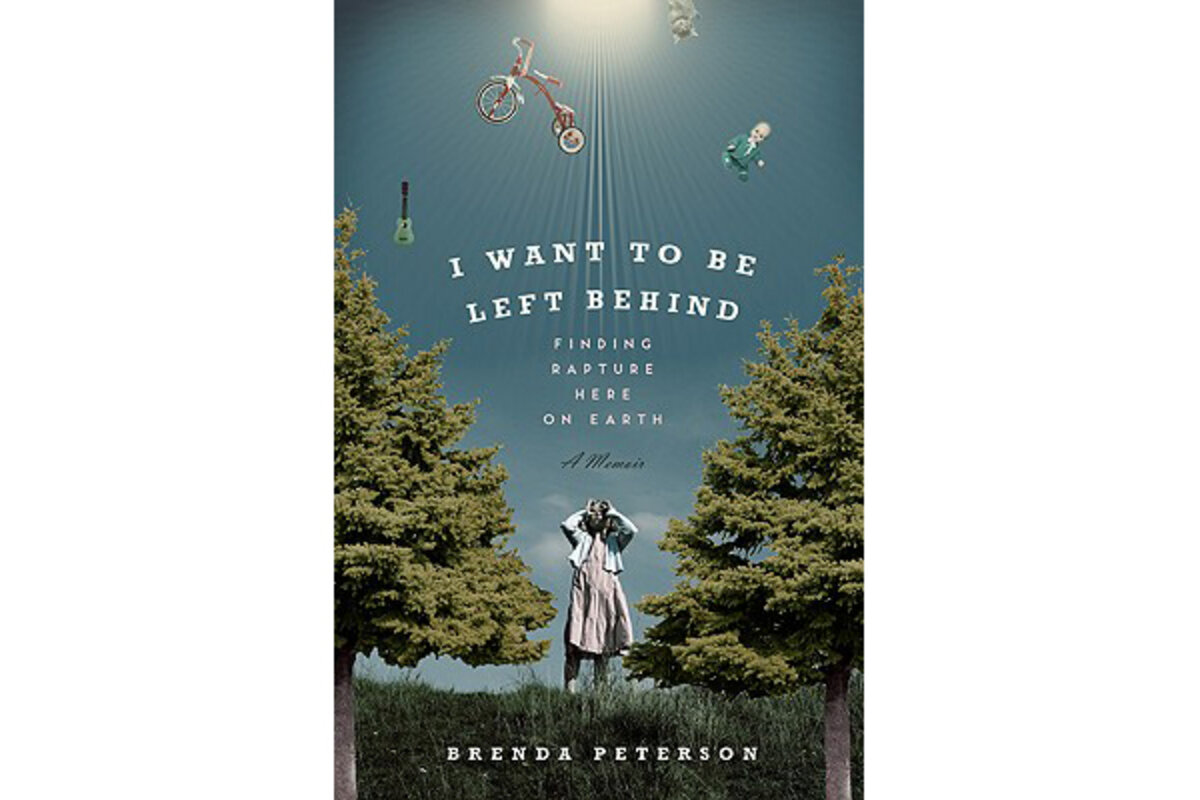

I Want to Be Left Behind

Loading...

Getting kicked out of fifth-grade Vacation Bible School helped Brenda Peterson realize who she really was: a nature-loving contemplative lodged in a community of conservative Southern Baptists.

The swift dismissal – prompted by her proposal that God could be found in an elegant flying squirrel – became a defining moment for Peterson. It instigated a lifelong quest to understand how she, moved more by the natural world than organized religion, could come from a family longing for the Rapture, when God-fearing folks would be subsumed into heaven.

Learning to live with her family’s mind-set while forging her own path is the marrow of Peterson’s new memoir, I Want to be Left Behind: Finding Rapture Here on Earth. Today a nature writer and environmental activist in Seattle, Peterson wraps her story in down-home warmth and a quick wit. Easing readers into Southern Baptist life, the moral of her story – that distancing herself from fundamentalism allowed her to refine her own budding beliefs – is only slightly eclipsed by a sprightly cast of characters who serve as bridges between the two camps. Her heroes, many of whom are both stereotypically conservative and dedicated to uncovering God’s glory on earth, will also enrich liberals’ understanding of fundamentalism as more nuanced than they may have imagined.

Unearthing commonalities between Peterson’s current beliefs (spiritual, not religious) and her heritage is a task requiring that Peterson, born in the High Sierra to a park ranger father and a church pianist mother (who later worked as a secretary at the CIA) first prove she is an authentic Southern Baptist. Her detailed, whimsical stories leave little doubt the girl grew up knowing fire and brimstone as well as sweet tea.

“[W]e were sweating even in our pedal pushers and bright flip-flops. There was the temptation of sprinklers chigg-chigging away on the church lawn and the waft of fried chicken and blackberry cobbler,” Peterson writes of that last day of Bible school in Virginia. “[M]y teacher, Mrs. Eula Shepherd, was a marvelous storyteller. Unlike my mother, who read us King James Bible stories every night, but at warp speed, Mrs. Eula was almost Shakespearean in her portrayals of prophets, holy wars and a cast of fascinating sinners.”

Peterson’s stories are gems, ranging from her participation in Southern Baptist Sword Drills (the “spelling bees for true believers. The Holy Bible was my sword,...”) to hanging from farmhouse rafters to loosen a perm.

Those who encouraged Peterson to see “the divine everywhere I looked” enter the story seamlessly. Jessie, a vivacious makeup artist and gardener in the Ozarks, had “Loretta Young lips.... Her high heels did not even sink in the mud.” The second wife of Peterson’s fundamentalist grandfather, Jessie also had an environmentalist’s take on praising God. “Jessie told me that God was in her garden and by tending her green world she was being a faithful servant,” Peterson recalls. Jessie also held some earthy views on redemption. “Most evil is ... forgetting ’bout anybody but yourself,” Jessie chastises Peterson for a transgression, even as she plunges into a river.. She pronounces, “Looks like you need some savin’.... [F]loat.”

With every move brought on by her father’s postings, bridges emerge. Peterson meets Pastor Joe – “more a man of spirit than religion – a mystic,” whose outspoken, ex-parole officer wife denies a biblical basis for the Rapture and teaches Peterson that “The Rapture was possible right here on earth. There are so many reasons to be left behind.” A literature teacher encourages Peterson to find links between Old Testament miracles of nature – a burning bush, whirlwinds – and writers who “looked for miracles and divine handiwork in the natural world.”

Peterson reflects anew on her father’s belief that “trees are God’s creation,” and their care his stewardship. “The spiritual solace that I sought in nature and my family found in religion might be much the same,” she realizes. Buoyed by the revelation, she brings elements from home – a love of gardening, folksy writing style – with her to a job at The New Yorker.

Not all co-workers appreciate it, and the liberal snobbery of some is as dogmatic as the family bias she runs from. Peterson’s experiences there make a good case for liberals to examine their attitudes, something she does, too – in an enlightening and funny comparison between fundamentalists and her adopted family, environmentalists. Both camps, she writes, are “Enraptured by doom... Holier than Thou... [and use] Blame, shame, [and] judgment.”

But how much should be generalized from Peterson’s experience? Her family’s frequent moves (making them “too cosmopolitan” for one Georgia community), careers with secular organizations, and their willingness to expose Peterson to folks like Pastor Joe suggest her parents might be fundamentalist outliers. (On a visit to New York at a time when few Southern Baptist churches were integrated, Peterson’s mother boldly drags her to an all-black Harlem Baptist church. Whereas Peterson is convinced that young black men there cast them a menacing eye, her mother makes lifelong friends.)

Today, Peterson and her family tend to check religion at the door when they meet yet share a handful of basic convictions – embrace life, be true to your morals, live passionately – that should probably be Scripture for all of us.

Sarah More McCann teaches religion and social justice at Cristo Rey Jesuit High School in Minneapolis.