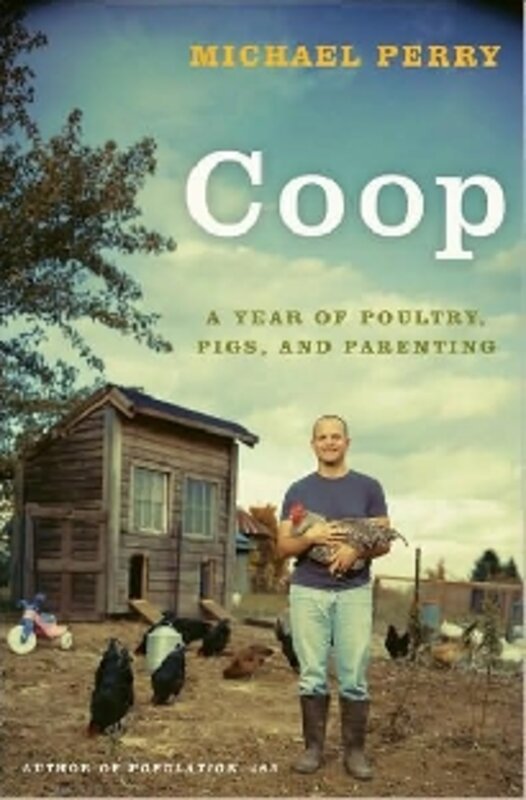

Coop

Loading...

Michael Perry’s life, now the subject of a third memoir, is not an extraordinary one. In less talented hands, the stories he recounts in Coop would merely have been the subject of an unusually busy holiday letter. But in Perry’s engrossing narration, they take on the heft of history, dotted with rueful humor and stories that beg to be performed aloud.

Coop, subtitled “A Year of Poultry, Pigs, and Parenting,” chronicles Perry’s move to a farmstead owned by his wife’s family, and their experiences acquiring livestock, awaiting a baby’s birth, parenting an older daughter, and facing unexpected deaths. It’s also the story of his own childhood on a farm: Perry was eldest in a large family that combined “a sliding scale” of birth and foster siblings.

The book’s beginning chapters jump among years and topics in the style of Perry’s past writings, and it’s a bumpy ride until readers settle into the rhythm of his memories. But as the parallels between past and present multiply, we see them more clearly as parts of the same timeless story of families and land.

Perry, a contributing editor to Men’s Health, is a professional writer but a gentleman farmer, confessing that he splits firewood to clear his mind as much as to heat the home, aware that “a simple move to the country” will not automatically equate to a simpler life. He is chronically “overdreamed and underbudgeted” as he juggles writing commitments with farm responsibilities such as a building a pig shelter and chicken coop.

His specific experiences are not universal, but the lessons he draws from them are, as with “the 37th time” he describes plans to save money by fencing the yard and acquiring sheep to serve as living lawnmowers and later sources of profit. His wife responds with her vision of the farmer on yet another speaking engagement, “talking about writing and raising sheep – meanwhile, I’m running through the brush with a howling six-month-old under one arm and dragging a bawling seven-year-old behind me with the other arm while we try to get the sheep back inside a hole in the cobbled-up fence.

“This is very hard on my pride, and pretty much on the money.”

Perry’s memories of childhood, as well, are painted with uncanny detail and with an adult’s comprehension. He spins a pages-long description of how his mother prepared popcorn for special Sunday suppers, rerunning crisp mental movies of how the popped kernels tumbled into the bowl “with a snowfall sound, an occasional old maid pinging the steel.” Now, recalling such meals, the generic food in the family pantry, and his mother’s rush even to spoon spilled milk back into a cup so it would not go to waste, he understands how his parents managed to provide.

Likewise, with a self-awareness that sometimes borders on self-consciousness, he watches “a scene composed by Andrew Wyeth and retouched by Edvard Munch” – his daughter weeping in a hayfield when he won’t buy expensive store-bought timothy grass for her guinea pig when she could collect and dry her own. He knows he is imposing a lesson in thrift and self-reliance, yet he also realizes he pushed the issue because he so loved haying himself as a child. When he details those days, he leaves us loving them too.

The book is no tell-all. Perry suggests that a farm kid remembers his first time behind a tractor with the same clarity as a first kiss, then devotes a mere half-sentence to the smooch and several loving pages to the tractor. But he does give a mature, matter-of-fact account of being raised in “an obscure fundamentalist ���Ǵ��� sect” that he remembers warmly but no longer follows, a sect through whose services he dozed not because he was bored, but “because I was cozy.”

Life cycles are the book’s unstated theme and Perry’s most powerful soliloquies are not births but his understated, gut-punching encounters with death. When tragedy hits him without warning, his perceptions guide us through feelings many will experience but few can articulate with such clarity: “Think of a feed bag filled with lead shot and allowed to achieve terminal velocity before the dead thump, the impact so echoless and mundane that for one dumb moment we fail to recognize the devastation for what it is.”

Rebekah Denn is a Seattle-based freelance writer.