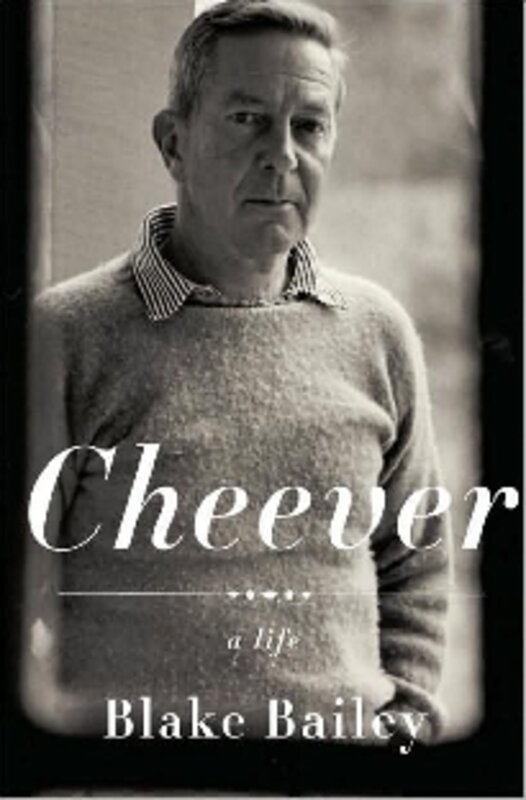

Cheever: A Life

Loading...

In the summer of 1934, the novelist John Cheever left the cozy confines of the writer’s colony at Yaddo, in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., and moved into a tenement on Hudson Street, in Manhattan – a neighborhood then so rough-hewed that Walker Evans, a friend of Cheever’s, eventually photographed the 22-year-old’s dingy flat for a series on Depression-era destitution.

Every week, John’s brother, Fred, would send him a tenner through the post, three of which went to rent; some to stale bread, milk, and raisins; and whatever was left to typewriter ribbon.

A few years earlier, Cheever managed to offload a single story to the New Republic, which had won him the welcome attention of a prominent editor named Malcolm Cowley. He had arrived in New York determined to write a novel, which he viewed – correctly, it turned out – as essential to his professional development. Still, the writing came slowly, and on bad days, Cheever would sit in Washington Square Park, wondering how long it might take a man to starve.

He became a fixture at uptown literary parties, where he would quaff Manhattans until he was hopelessly drunk.

“Sobriety seemed out of the question,” Blake Bailey reports in Cheever: A Life, his expansive, wonderfully written biography of this brilliant yet deeply troubled man. Bailey quotes one of Cheever’s first girlfriends, who remembered that the young writer, “simply never faced himself, and when he did he didn’t like what he saw. And nothing relieved him.”

This last statement is not entirely accurate. Cheever had two sources of respite.

One was sex, an activity at which he was endlessly – and enthusiastically – profligate. He slept with editors, writers, married women, and, at least once, Walker Evans. Sometimes Cheever’s escapades sent him spiraling into melancholy – the “megrims,” he called them – but more often they served to take his mind off the grimier aspects of quotidian existence.

His other great pursuit, of course, was writing, a craft he viewed with equal parts reverence and fear. Writing was a way to expurgate at least some of the demons he’d collected from a young age.

And yet, if Cheever knew he was meant to write, the very act itself often proved violently agonizing. There was salvation in fiction, he believed, but it was hell to get there. Cheever, who published “Falconer,” perhaps the greatest novel of the late 20th century, lived a life marred by the most savage emotional trauma.

The heir to one of the storied names in New England history, Cheever’s parents, Frederick and Mary, managed to fritter away most of their money and sunk into a very public ignominy John would never forget. Although he often affected a lordly Yankee air, Cheever left his hometown of Quincy, Mass., early on and returned only twice, Bailey notes, once for his brother’s funeral, “and once for his own.”

Cheever once wrote, “I have no biography. I came from nowhere and I don’t know where I’m going.”

Where did he go? Well, just about everywhere an aspiring writer could imagine. Unlike the other sad, young literary men crowding Manhattan at the time, Cheever did not have a Harvard degree – he had no degree at all – and yet his fiction was so pressingly precocious, so fantastically knowing, that, within a few years of his arrival in New York, he found himself surrounded by high-powered editors and agents.

They pressed him to write, and he obliged: “The Way People Live,” an early collection, was followed in the ’50s by the “The Wapshot Chronicle” and, later, by the enigmatic “Bullet Park.”

By the time he published “Falconer,” in 1977, he was one of the pillars – John Updike was another – of the modern literary establishment. He appeared on the cover of Time in 1964, picked up the Pulitzer Prize in 1979, and the National Medal of Literature in 1982, just before his death. He wrote 121 stories for the New Yorker, each of them a small masterpiece of observational wit.

Like Richard Yates, author of “Revolutionary Road,” and the subject of another Bailey biography, John Cheever’s primary subject was the corruptive influence of the suburbs and the horridly normative patterns of city life. He believed in the possibility of redemption, but doubted that most men had the moral strength to make it that far.

Most of all, he doubted himself. He was buffeted by addiction and melancholy; from an early age, he felt more attraction to men than to women and he spent the rest of his life unsuccessfully wrestling with his sexual urges. Only after he was dead and gone did his children learn the truth. (His long-suffering wife, apparently, had a pretty good idea of Cheever’s predilections.)

Bailey’s biography, which relies heavily on Cheever’s personal journal and letters, is not an easy book to read. Bailey spares us none of Cheever’s struggles.

In an essay published posthumously last week in the New Yorker, John Updike – an acquaintance of Cheever’s – regretted Bailey’s insistence on documenting his subject’s every transgression. It makes the biography, he lamented, “a heavy, dispiriting read, to the point that ... I wanted the narrative ... to hurry through the menacing miasma of a life, which for all the sparkling of its creative moments, brought so little happiness to its possessor and those around him.”

That seems to me an ungenerous assessment. It’s true that “Cheever: A Life” is a hard and bracing read, and that Bailey is indeed unstinting in his depictions of Cheever’s travails. And yet, all that darkness helps pull the genius – “the sparkling of the creative moments,” as Updike has it – into relief. To read Bailey on Cheever is to arrive at a much fuller appreciation of a deeply gifted chronicler of American life.

Matthew Shaer is a Monitor staff writer.