Germany’s real-life melodrama

Loading...

Who was Richard Wagner, really? A brilliant composer who reshaped modern music? A wildly incoherent thinker whose muddled ideas contributed to the Holocaust? Or an insecure eccentric, a celebrity who slobbered over patrons, abused friends, and sometimes screamed if his guests talked to one another instead of to him?

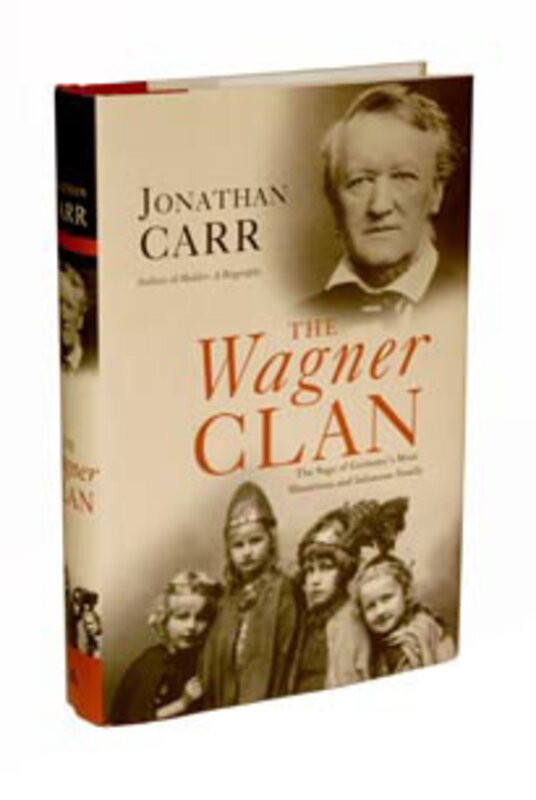

The correct answer may be all of the above and that’s just part of what makes Jonathan Carr’s The Wagner Clan so intriguing a read. The rest of the allure derives from the Wagner family themselves. The book’s subtitle is “The Saga of Germany’s Most Illustrious and Famous Family” and saga is indeed the mot juste.

Take a backdrop of intergenerational intrigue, adultery, and betrayal. Toss in a spoiled orphan, a handful of opportunists, some Nazis, and a glamorous family business and you’ve got the Wagner epic.

But Carr, a British journalist and music biographer (“Mahler: A Biography”) now living in Germany, prevents this story from sinking into the merely sensational. His nuanced account seeks to bring a fair balance to some of the wild charges associated with the Wagner story and at the same time offers a compelling account of Germany itself from the early 1800s on up.

Richard Wagner, was born in Leipzig in 1813. The Europe of that time was a turbulent place and he, it seems, never met a revolution he didn’t like. Between supporting unsuccessful insurgents and racking up debt Wagner was often on the run.

“A scoundrel and a charmer he must have been such as one rarely meets,” wrote American composer Virgil Thomson, and so it would seem. When stability finally arrived in Wagner’s life it came by the grace of two somewhat dubious connections. One was his adulterous relationship with Lizst’s illegitimate daughter Cosima. This (once both had jettisoned their first spouses) turned into a lasting marriage, resulting in three children and Cosima’s lifelong devotion to Wagner’s legacy.

The other was the patronage of Germany’s King Ludwig II (“the mad king”) who believed in Wagner’s genius and bankrolled his schemes, including building him an opera house in the small German city of Bayreuth.

There, Wagner was able to supervise the production of his own operas and stage his own festivals. When he died in 1882, the wily Cosima took control with their son, Siegfried, himself gifted as a composer and a director.

But when Siegfried, late in life, married Winifred, a young British orphan, she opened the door to an ugly chapter in family history. In 1923, after Siegfried’s death, Winifred fell hard for Adolph Hitler.

The Nazi leader was an avid enthusiast of Wagner’s music and soon became “Uncle Wolf” to the family, cuddling and coddling Siegfried and Winifred’s four children (even their snippy little Schnauzer dog adored him) and enjoying regular trips to Bayreuth.

Carr debunks the notion that Wagner’s music had a special resonance for Nazis. (He points out that most of Hitler’s men sat through an opera only under orders.) But he does not deny either Wagner’s erratic antisemitism (he denounced Jews as often as he befriended them), Cosima’s virulent antisemitism, or Winifred’s unrepentant, lifelong infatuation with Hitler.

One of the most amazing aspects of the Wagner story – given the family’s close ties to Hitler – was the fact that, despite “denazifaction,” they regained control of the theater and the annual Bayreuth festival after the war. Since having regained that control, they’ve quarreled much over it (and great-grandson Wolfgang’s 57-year tenure as director draws plenty of fire) but there’s no denying the festival’s success: There is a 10-year waiting list for tickets.

It makes an astonishing coda to a remarkable tale.