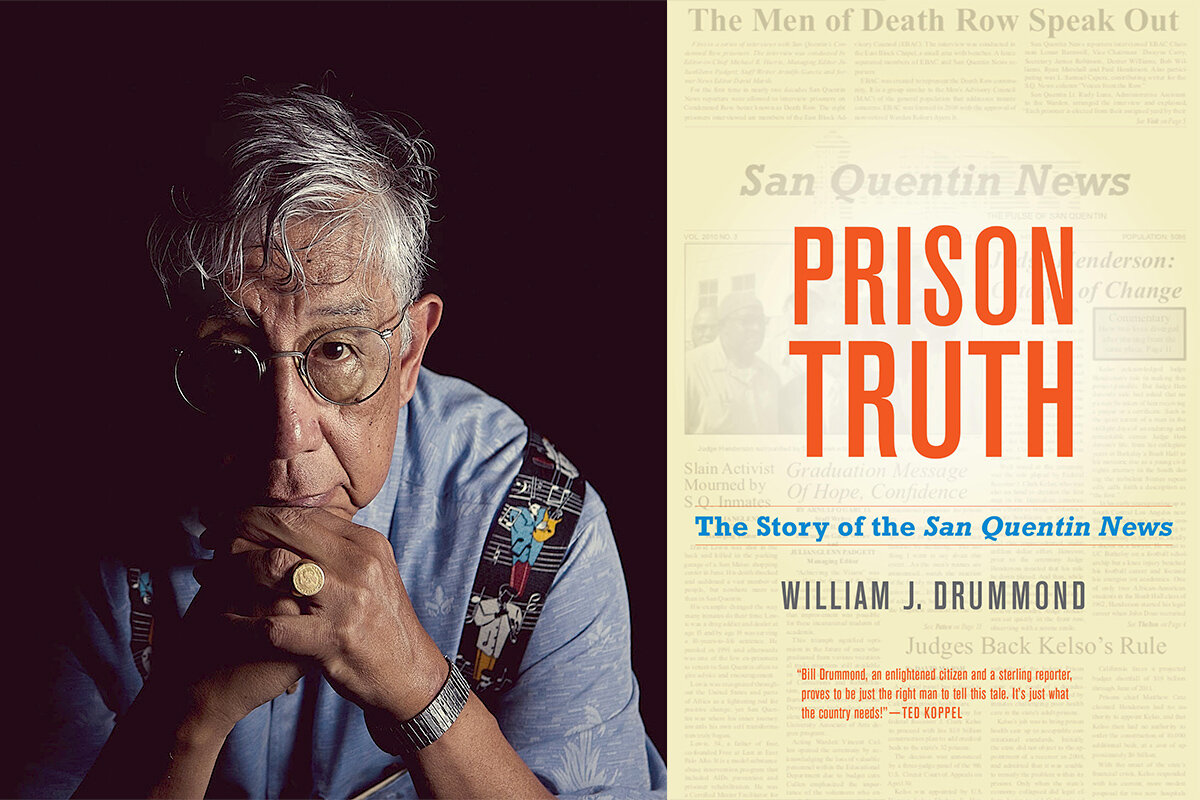

Q&A with with William J. Drummond, author of ‘Prison Truth’

Loading...

William J. Drummond, a pioneering African American reporter in the 1960s and currently a journalism professor at the University of California, Berkeley, began mentoring prisoner journalists several years ago. He writes about the experience in his book, “Prison Truth: The Story of the San Quentin News.” In an interview, he talked about the power of storytelling behind bars.

Q:¬ÝWhat impressed you about the incarcerated men with whom you worked?

I was amazed at their level of interest in journalism and the attention they paid to the topics.

I gave them an assignment that I’ve routinely given in every writing class I’ve ever taught: Write your own obituary. The results were enlightening. They often portrayed themselves as the heroes in their own life stories. They had a tough beginning, and they got in trouble, but something miraculous happened. Then they went back to their communities and were leaders and positive forces.

I left the door wide open to how they portrayed their own demise, and some did heroic things to prove their worth, like saving the life of a prison staff member.

This was a huge personal insight, more than I’ve gotten in my years of covering what we used to call the underclass. I ponder it all the time. Nobody is all good, and nobody is all bad.

Q:¬ÝWhat sort of backgrounds do these men have?

They were in prison for every possible offense, and they were typically in their 40s, with some in their 30s, 50s, and 60s. Many in their 40s had come into prison during California’s crackdown on crime 15 to 20 years ago. And a lot were out on the street and involved in one form or another in personal wars, gang wars, or drugs.

Q:¬ÝHow do they compare with the undergraduates you teach?

It’s not like a normal classroom where everybody’s looking at their watch. The prisoners really, really want to be there. These guys are great conversationalists compared to the students I encounter now. We’ve got a whole generation of kids who might be texting someone standing next to them and don’t have the ability to tell a story, to just sit down and entertain people. In prison, you have nothing better to do than listen and talk, so they can be very entertaining conversationalists.

Q:¬ÝYou brought student journalists inside the prison. What happened?

They were really intimidated at first. And then, little by little, they develop friendships and learn how to conduct conversations.

Q:¬ÝHow did the San Quentin News avoid censorship or shutdown?¬Ý

The prison is under no obligation to allow a newspaper to be produced. That‚Äôs the reality. There was an enlightened warden who laid down the rules: If the governor sees the paper one day and shuts it down because it‚Äôs gone too far, you will have failed. And you do not want to fail. So there is censorship. But it‚Äôs self-imposed.Ã˝

The men concentrate on stories of rehabilitation, redemption, and success, and there’s a big audience for that. It corresponds with San Quentin’s new reputation as a rehabilitative environment that helps people to go home. That’s why prisoners want to go there.

Q:¬ÝThe pandemic may change the rules about personal interactions behind bars. What might come next for the San Quentin News, which seems to be on hiatus?

The newspaper‚Äôs impact goes beyond just publishing a thousand copies. It has created a partnership between the prison management and a group of prisoners. I don‚Äôt know if they‚Äôll let us work with prisoners face to face. But the newspaper really needs to be saved.Ã˝

The San Quentin News can be read online at .Ã˝