From MLK to Black Power: Books trace the Civil Rights Movement

Loading...

In a sermon titled “Loving Your Enemies” that he delivered often in the early 1960s, Martin Luther King Jr. insisted that he had taken the biblical command to heart. “Put us in jail, and we will go in with humble smiles on our faces, still loving you,” he preached. “Bomb our homes and threaten our children, and we will still love you ... But be assured that we will wear you down by our capacity to suffer.”

In the years leading up to King’s 1968 assassination, he was jailed 29 times, assaulted repeatedly, and threatened constantly. He had to contend not only with die-hard segregationists but, appallingly, with his own government. The FBI, convinced he was being influenced by communists, tapped his phones. When the bureau found evidence not of communism but of the civil rights leader’s marital infidelities, it used that information to try to destroy him.

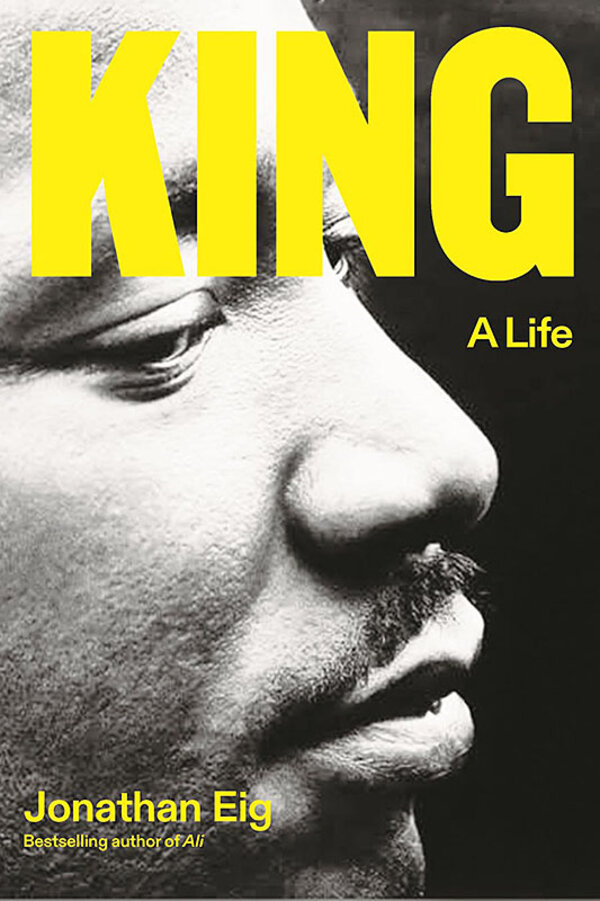

Jonathan Eig covers this ground, and much more, in his sweeping, edifying “King: A Life,” one of three recent, excellent civil rights-themed books. Eig’s is the first major biography of King in decades, and with the help of newly available sources – from declassified FBI files to recently discovered audiotapes recorded by his widow, Coretta Scott King – the author presents the iconic MLK, who remained steadfastly committed to nonviolent protest, in full.

Why We Wrote This

As more primary sources become available – including declassified government documents – the history of the Civil Rights Movement is becoming richer and fuller.

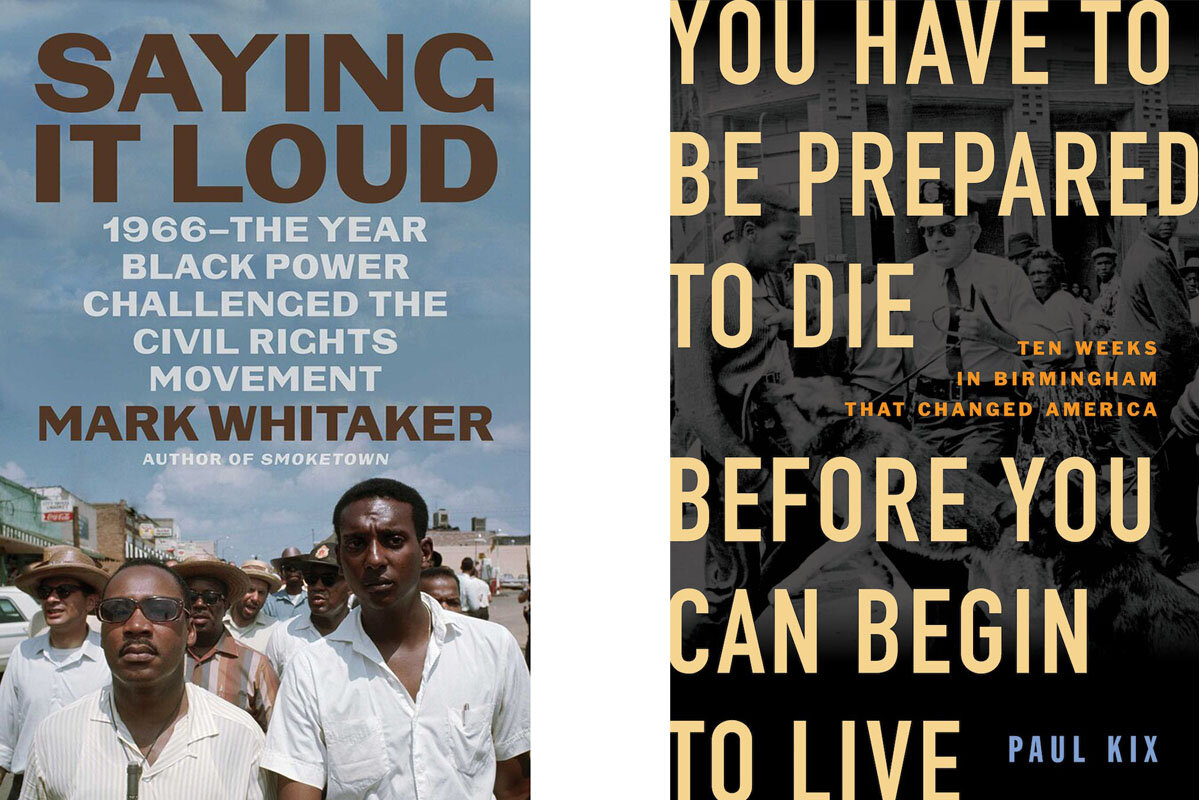

The two other books focus on smaller pieces of the civil rights story. In the inspiring “You Have to Be Prepared to Die Before You Can Begin to Live: Ten Weeks in Birmingham That Changed America,” author and journalist Paul Kix charts the 1963 campaign by King’s Southern ���Ǵ��� Leadership Conference to end segregation in Birmingham, Alabama. Mark Whitaker’s riveting “Saying It Loud: 1966 – The Year Black Power Challenged the Civil Rights Movement” chronicles a turning point, when younger activists like Stokely Carmichael and Huey Newton increasingly repudiated King’s nonviolent tactics.

Eig, whose previous subjects include Muhammad Ali and Lou Gehrig, argues that “in hallowing King we have hollowed him”; his humane portrait presents MLK’s frailties alongside his heroism. The cradle-to-grave biography covers King’s relatively privileged Atlanta upbringing and his fraught relationship with his domineering father, which Eig cites as the source of King’s insecurity and occasional depression.

The author’s description of the successful yearlong Montgomery bus boycott, which began in December 1955 and propelled King into a leadership role, is thrilling. The Alabama city was so committed to segregation that it closed all of its public parks for six years rather than integrate them. But at only age 26, King was, Eig writes, “the right man at the right time” to lead the difficult campaign to end segregated seating.

“If we are wrong, the Supreme Court of this nation is wrong,” MLK preached to an adoring crowd. “If we are wrong, the Constitution of the United States is wrong. If we are wrong, God Almighty is wrong.”

King’s stature rose after the boycott, reaching its pinnacle when he delivered his indelible “I Have a Dream” speech on Washington’s National Mall in August 1963. In later years, however, his attempts to take on poverty and housing discrimination in the North cost him liberal white support. He was unprepared for the violent resistance he encountered when he tried to organize protests to desegregate Chicago neighborhoods. “I think the people of Mississippi ought to come to Chicago to learn how to hate,” he said.

His increasingly vocal opposition to the Vietnam War further eroded King’s popularity and led to a bitter break with President Lyndon Johnson, who had signed landmark civil rights legislation in 1964 and 1965. King’s mood grew dark in the months before he died. “He said people expect me to have answers and I don’t have any answers,” his wife later recalled.

Attacks on peaceful marchers

King is a major player in Kix’s book, but not the only one. “You Have to Be Prepared to Die Before You Can Begin to Live” covers the Southern ���Ǵ��� Leadership Conference’s bold plan to, in the author’s words, “subject itself to the full wrath of Birmingham, in the hope that white people outside the city might at last see, through the SCLC’s suffering, the plight of all Blacks in America.” The source of that wrath would be the virulently racist Bull Connor, the city’s longtime public safety commissioner. In large part because of Connor, Kix writes, Birmingham “was not so much a city in 1963 as a site of domestic terror.”

King’s Birmingham colleagues included Wyatt Walker and James Bevel and local pastor Fred Shuttlesworth. The organizers often clashed, and the conflict-averse King could be painfully indecisive. The campaign, which initially flagged, was energized by the participation of children, a fiercely debated decision over which King agonized. After being trained in nonviolent direct action, 973 young marchers were arrested in one day for parading without a permit.

The SCLC gained leverage when it became clear that waves of peaceful protesters would keep coming, despite Connor’s use of fire hoses and police dogs to deter them; the city did not have enough jail space to contain them. (It was from a Birmingham jail, of course, that King wrote the blistering, enduring letter declaring that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”) The movement gained worldwide sympathy when newspapers published a sickening photograph of a police dog lunging at a Black teenager. The attacks on peaceful marchers finally galvanized John and Robert Kennedy to support civil rights legislation.

Rise of Black Power

In “Saying It Loud,” journalist and author Whitaker focuses on a more radical set of activists, many of whom had lost patience with King’s slow and steady approach as movement leader. “The presence of Malcolm X hovered over them,” Whitaker writes. For them, King’s mantra of nonviolence had became synonymous with ineffectuality.

“We’ve been saying ‘Freedom Now’ for six years and we ain’t got nothing,” Carmichael, the most prominent figure in Whitaker’s book, famously told an energized Mississippi crowd in1966. “What we’re gonna start saying now is: ‘Black Power’!”

The firebrand had become president of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee just weeks before when the younger members of the group ousted the moderate John Lewis. (After a painful debate, SNCC later voted to expel all white members from the organization.) Carmichael’s defiant “Black Power” chant, the author writes, “made him a nationally recognized figure virtually overnight.” It helped inspire Newton and Bobby Seale to arm themselves and create the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in California.

Whitaker insightfully captures the young activists’ frustration with King – many of them mocked him with the nickname “Da Lawd” – as well as their sense that nonviolence left them vulnerable to white brutality. He follows the threads of Black power from the establishment of Black studies programs in higher education to the reactionary rise of conservative politicians like Ronald Reagan, who courted the “white backlash” vote in his 1966 run for California governor.

The Civil Rights Movement will continue to provide fertile material for authors. We can expect new accounts as additional information becomes available. For instance, we’ll learn more about the FBI’s surveillance of King when additional records are unsealed in 2027. Moreover, different perspectives become appreciated over time. Women’s importance to civil rights has long been downplayed, but these histories properly credit women for their contributions, whether it’s Whitaker profiling the formidable SNCC staffer Ruby Doris Smith Robinson or Eig highlighting Coretta Scott King’s own work on behalf of the movement.

Finally, the battles of our own time remind us of the relevance of this history, and the lessons it has to teach. These books are up to the task.