A naturalist figured out climate change in 1799. The world forgot him.

Loading...

Few people today remember Alexander von Humboldt, but the Prussian naturalist predicted climate change back in the early 19th century. “He’s the forgotten father of environmentalism,” says historian Andrea Wulf.Мэ

During Humboldt’s travels through Venezuela in 1799, he noticed that farmers in the Aragua valleyМэwere deforesting the region to grow indigo. As a result, the nearby lake was drying up. Later, in a letter to President Thomas JeffersonМэdated June 1804, he wrote, “The wants and restless activity of large communities of men gradually despoil the face of the Earth.”

It was one of the first Western observations of human-caused climate change, according to Wulf. Environmentalists and scientists like Charles Darwin, John Muir, and Henry David Thoreau were heavily influenced by his writings, which were widely read during his lifetime.МэWulf wanted to raise Humboldt’s profile for today’s readers. So she wrote “The Adventures of Alexander von Humboldt,” a lush and meticulously illustrated history of his South American expedition.Мэ

Why We Wrote This

Driven by a restless curiosity that resisted the confines of any one scientific discipline, Alexander von Humboldt offered the world a kaleidoscopic view of the wonders of nature. Andrea Wulf and Lillian Melcher bring this “forgotten father of environmentalism” to life in a lush graphic novel.

“I grew up in Germany, so we heard about [Humboldt] as an adventurer, or maybe a botanist,” Wulf says. “But no one talked about him as the man who had predicted harmful, human-induced climate change. So that became the thing that got me going.” She’s also the author of “The Invention of Nature,” a 2015 New York Times bestselling nonfiction book that delves more deeply into Humboldt’s life and influence.Мэ

“The Adventures of Alexander von Humboldt” stands apart with its rich visual presentation: It’s filled with Humboldt’s own drawings, maps, and writings, all sourced from the Berlin State Library’s digitized collection of his journals. Those are juxtaposed with a dizzying array of reproductions, including pressed botanical samples, landscape paintings, and photos. And it’s all stitched together by the artwork of Lillian Melcher, a recent Parsons School of DesignМэgraduate.

“[Humboldt] was one of the first people to make science popular and accessible, because he used infographics in all of his books,” says Melcher. She believes strongly in following in his footsteps to increase scientific literacy. “I think that combination of science and art is a better way to learn,” she says.

Wulf and Melcher collaborated to storyboard the book, but “Humboldt was our third collaborator,” Melcher says.Мэ

Each page represents weeks’ worth of research. “Andrea and I are definitely the same kind of nerdy, where we just want accuracy. We want to know all the little details,” Melcher says.

For example, the scanned pages of Humboldt’s diary that appear as background images on most pages of the book actually correspond to the events taking place in the story. When Humboldt’s boat capsized in the Orinoco River, his journals were stained with river water. Wulf and Melcher used reproductions of those diary pages to collage an image of the river, and Melcher drew Humboldt jumping into the pages to rescue his belongings.

“He’s jumping through that watermark to rescue his diary, but it’s [also] the real watermark,” says Wulf. “It’s this double sense and I just love it.”

Мэ

Humboldt’s interests were so wide-ranging that he found it hard to settle into a specific discipline. (That’s perhaps one of the reasons he fell into obscurity: As scientific thought progressed, narrower focuses took precedent.) The structure of “The Adventures of Alexander von Humboldt” is a true reflection of his restless curiosity – always varied, sometimes digressive, it’s a kaleidoscopic view into the diverse, fascinating, and occasionally brutal landscape of the South America that he encountered.Мэ

Intrinsic to Humboldt’s writings were his critiques of imperialism and slavery, as well as of environmental degradation. With startling prescience, he pointed out the economic, environmental, and human costs of slavery and silver mining in “Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain” and “Political Essay on the Island of Cuba.” Both are introduced in Wulf’s and Melcher’s book.

Importantly, he allowed his passion for nature to influence and color his work. “If I look at [today’s] climate change debate in the political arena ... what I’m really missing is that no one dares to talk about the wonders of nature,” says Wulf. “[Humboldt] says we need toМэfeelМэnature. We need to use our imagination to understand nature. ... And this aspect of his work, I think, is what makes it incredibly relevant today.”

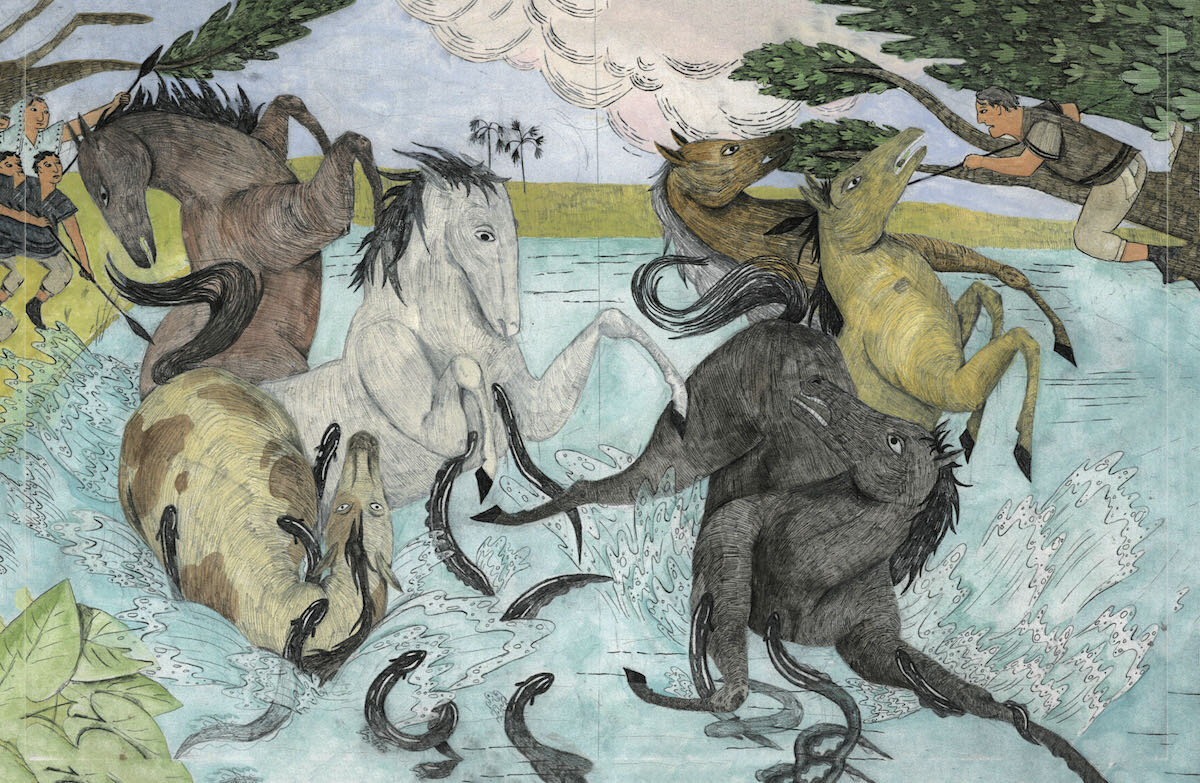

There’s no doubt Humboldt was intrepid. He fearlessly placed himself in harm’s way to gather knowledge, even if that meant climbing active volcanoes, crawling into mines, and prodding electric eels. When a ship he was on sailed into a hurricane with 40-foot waves, he sat down to calculate the exact angle at which the boat would capsize. Death would be better experienced methodically, he reasoned. The ship stayed afloat.

“The Adventures of Alexander von Humboldt” gives a true sense of the global scale of his imagination, and of the indomitable drive that enabled him to disseminate the scientific information he gathered to the next generation of scientists, writers, and artists. Western civilization at large is only now beginning to understand what Humboldt intuited in the early 19th century: “In this great chain of causes and effects, no single fact can be considered in isolation.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correctly state the name of the school attended by Lillian Melcher.